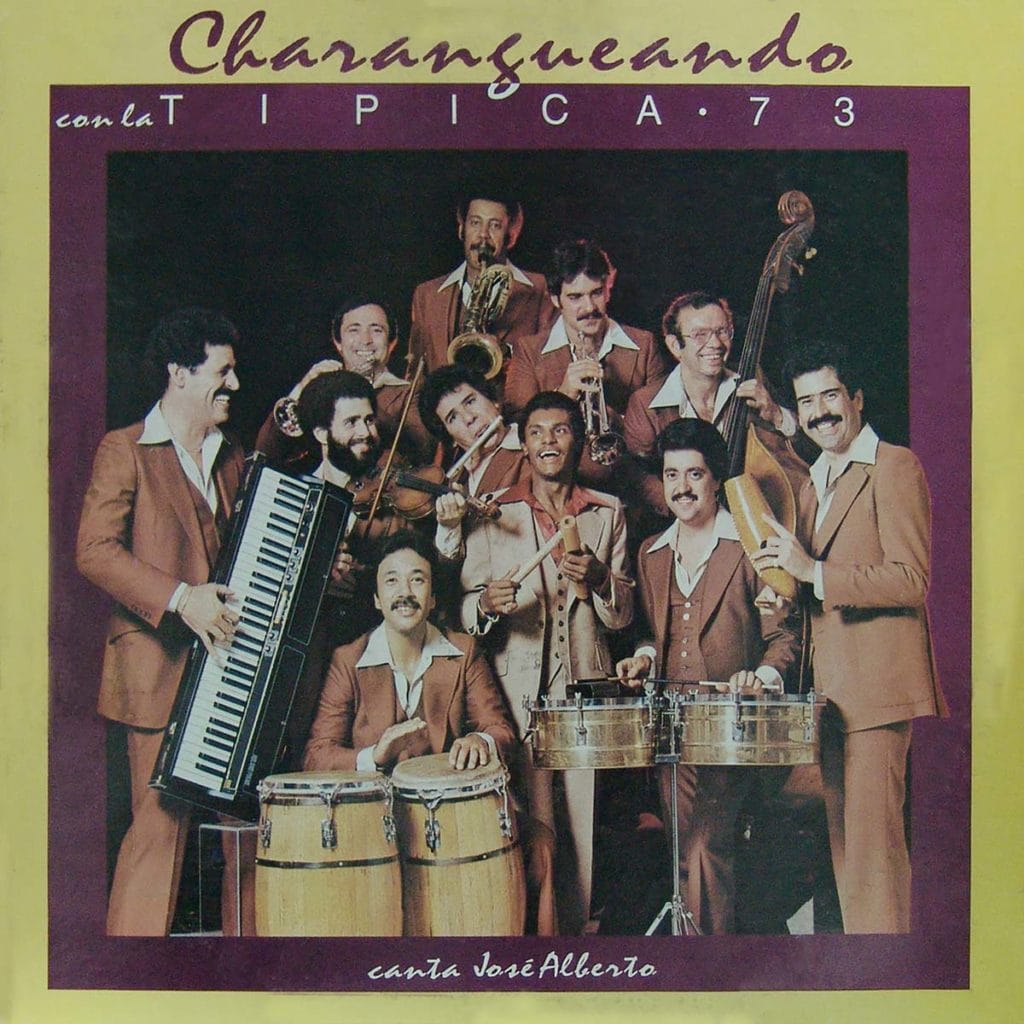

In his liner notes for the original LP, Sonny Bravo wrote that the Típica 73 repertoire and arrangements heard on this recording actually came from informal Monday night jam sessions at a New York club. “There were no charts then,” wrote Bravo describing the band’s collective arranging style. We relied mainly on old charanga standards. I would start off with a riff…then Johnny would come up with a break. After the montuno Rene would improvise a horn mambo, etc.” Bravo wrote the charts out for future performances, but it really was a group effort when it came to writing the arrangements.

The musicians associated with Típica 73 are amongst the finest in the history of New York’s Cuban popular music scene, and Latin music enthusiasts are lucky that this group came together on those Monday nights to play. The band’s first records were not actually in the charanga style, but closer to a conjunto or orquesta. What separated Típica 73 from its contemporaries was a deep knowledge of Cuban popular music and an interest in staying current with the music on the island after 1959. The band frequently recorded contemporary Cuban hits, but they were not content to merely copy and instead infused their music with humor, inside jokes and musical innovations.

It is a misconception that this album was recorded after the release of 1979’s Intercambio Cultural, when the band traveled to Cuba to record with Cuban musicians. In fact, this album was recorded in the summer of 1978 but Fania pushed its release to 1980 to capitalize on the band’s publicity with the Cuban album and trip. When I spoke with Bravo in September 2005 he shared these insightful words about the Cuba trip: “Going to Cuba cost me the band, but if I had to do it over again I would do it exactly the same (way).” After the trip, the band stopped playing for Cuban-American groups and certain engagements were publicly threatened with violence as a result of traveling to Cuba and “consorting with communists.” This is ironic especially considering that the 1990s was a decade of much interaction between Cuban and U.S.-based musicians.

Born in New York, Sonny Bravo (born Elio Osácar) was the son of tampeño, Santiago “Elio” Osácar, of the Cuarteto and Conjunto Caney. Joining Caney a year after his father passed away, Bravo was active in Miami during the 1950s performing opposite Orquesta Aragón, Roberto Faz and Benny Moré. He would later go on to many high-profile musical associations. Bravo is a direct link to the past and future of Latin-Caribbean music and the same could be said for the musicians who have filled Típica’s ranks over the years, such as Orestes Vilató, Johnny Rodríguez and Mario Rivera, and others. Hopefully, subsequent re-issues will cover the success and dramatic split that punctuates the history of this unique musical group. Enjoy!

A standard in José Fajardo’s repertoire, Busco una Chiquita is given a Típica 73 makeover. Bravo fleshed out the original line and Alfredo de la Fé picks out new guajeos on the violin and uses a wah-wah pedal. In a twist on the original lyrics, the band capitalizes on the salsa craze singing “Mi chiquita si tu me quieres, ven conmigo a bailar la salsa.”

Tito Puente’s A Donde Vas features a modern jazz-influenced piano introduction by Bravo. This swinging song is a tasty guajira that showcase Dick “Taco” Meza on the flute. The vocals evoke the style of Orquesta Aragón but the band personalizes the song: “Te fuiste con la Típica 73.”

This version of Rafael Hernández’s Cachita has become the standard reference when musicians play the tune today. Here you can hear how Bravo’s jazzy harmonization of the melody and the overall swinging effervescence of the band exemplify the Típica 73 sound throughout the solos, montunos, mambos and moñas.

Yo no camino mas is another charanga warhorse performed by many groups to this day, both within Cuba and elsewhere. Típica was always comprised of new and established musical talent and listening to a young José Alberto “El Canario,” it is easy to see how his current style was shaped as a result of his time with the band.

Tunas serves as a showcase for the individual personalities of the band members. Bravo’s tasty solo is a textbook for would-be pianists— “guarapo en teclas.”

In the introduction to Chanchullo, the band deviates from the charanga tradition through the use of modern harmony (whole tone scales) and sonic manipulation (echo effects). The song also treats listeners to inventive solos by Alfredo de la Fé, Rene Lopez, Joe Grajales, Johnny Rodríguez and Nicky Marrero.

In Bravo’s words, the traditional Comparsas medley that concludes the album was conceived of as a “despedida.” The beginning starts with a familiar Típica arrangement technique: Bravo and de la Fé improvising freely over the rhythm section. This gives way to a straightforward rendition of several Cuban carnival songs but as always with a few twists à la Típica.