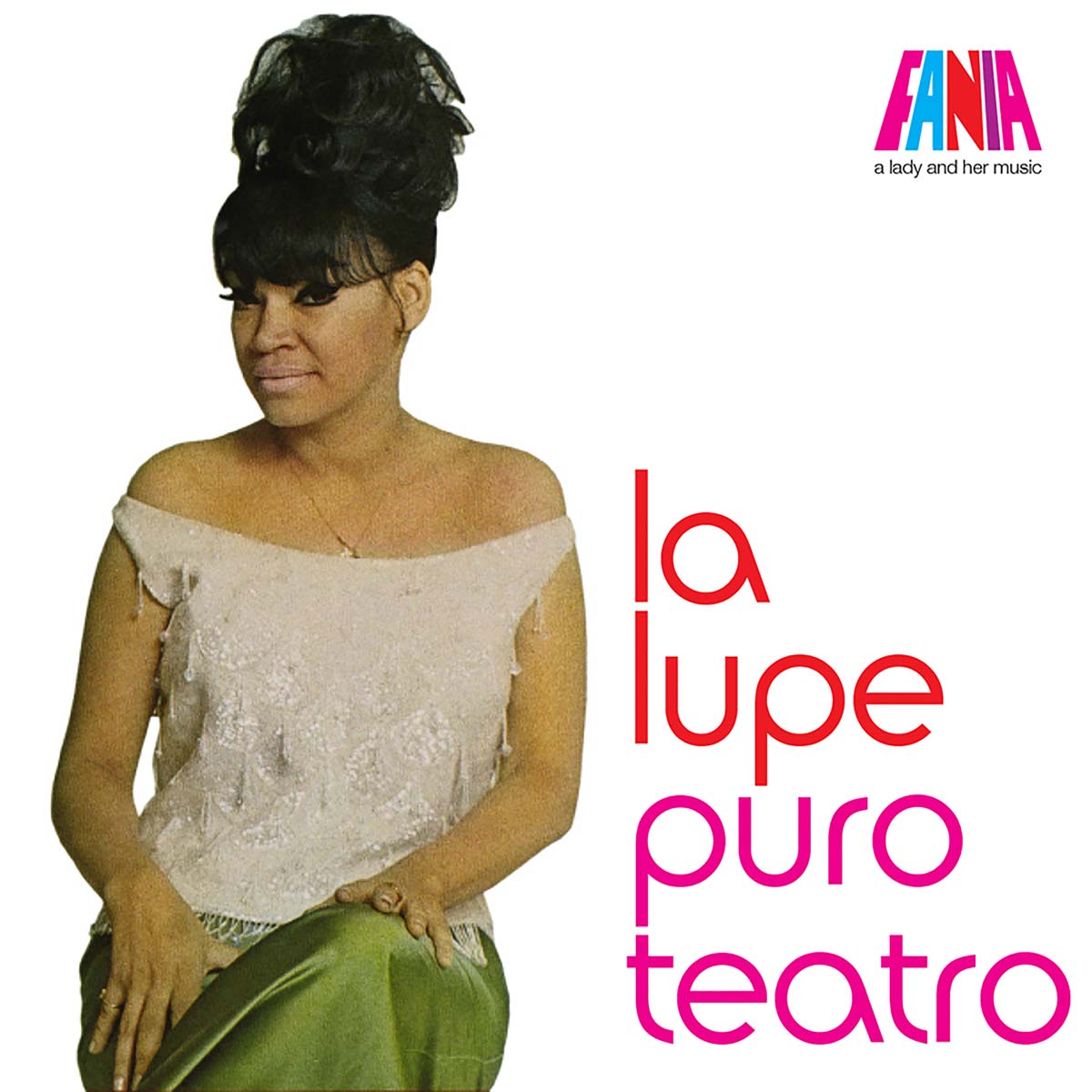

La Lupe Puro Teatro – A Lady And Her Music Liner notes by Matt Rogers “I think people like me,” the legendary La Lupe told Look magazine in 1971, “because I do what they’d like to but can’t get free enough to do.” True, some would say La Yi Yi Yi—one of the most electrifying singers to ever blitz Planet Earth—was free spirit incarnate; others would say she was simply possessed. Literally. No surprise, given the voluptuous vocalist’s onstage inclination to bounce off walls, tear away her clothes, throw shoes and jewelry at her band, and claw, bite, and scratch herself, all the while continually belting tunes with orgasmic heat, all as if in a trance. “I sing with delirium!” she once sang, and she did, turning each song into a full-fledged drama. Some criticized her for dressing like a streetwalker, while others embraced her bold sexuality.

Her performances onstage and on wax reflected her tumultuous life offstage and were indeed—like the name of one of her most famous songs—puro teatro. A melting pot of Edith Piaf, Eartha Kitt, Olga Guillot, Tina Turner, and Nina Simone, the singer’s tempestuously elastic voice could both coddle and torch any genre. Whether interpreting boleros or son montunos, pop schlock or rock-and-roll ditties, jazz standards or Broadway show tunes, La Lupe simply couldn’t contain the music within herself. And no one—be it Fidel Castro, Mongo Santamaria, Tito Puente, or Morris Levy—could ever, no matter how hard they tried, contain her philharmonic energy.

She was a wrenching tug-of-war between impulse and craft, be her platform the street, club, or recital hall. Such grand musical drama took her around the world and reportedly drew international celebs and sophisticates like Marlon Brando, Ernest Hemingway, Simone de Beauvoir, Tennessee Williams, Picasso, and Jean-Paul Sartre into her court, but anyone who ever bore witness—from riffraff to royalty, young and old, whether in her native Cuba, the USA, or Latin America—never forgot her. Or did they? Many thousands came to her shows—from Birdland to the Palladium, Carnegie Hall to Madison Square Garden—and millions of fans bought her LPs, while millions more saw her on TV. Yet, despite the renown and being crowned the “Queen of Latin Soul,” despite recording a dynamic slew of two dozen albums, one of the twentieth century’s most charismatic entertainers died a pauper’s death. Once upon a time, long before popular TV host Mike Douglas introduced her as a legend whose style was “sex, fire, soul, and voodoo,” long before Look magazine stated that “she makes Jane Birkin sound like a puppy,” long before she became associated with drag queens and drugs, and before one Cuban publication declared her “a psy- chosomatic case that divides Cuba in two,” and most definitely pop culture eons before today’s masses went all ga-ga-goo-goo for La Lupe’s lineage, Lady Gaga, La Lupe was born Lupe (though some sources say Guadalupe) Victoria Yoli Raymond in San Pedrito, a town in the southern part of Cuba near Santiago de Cuba.

There seems to be an agree- ment about the day of La Lupe’s birth—December 23—however, perhaps befitting such a controversial figure, the actual year of her birth appears to be up for debate, as most sources say either 1936 or 1939. Archival footage from La Lupe’s funeral shows 1936 as the date given on her casket, while her tombstone at St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx gives her birth year as 1939. So rural was her hometown that she once remarked, “I was born in such a small town, nobody knew about it until I left.” In Ela Troyano’s excellent PBS documentary La Lupe – Queen of Latin Soul, Norma Yoli, Lupe’s sister, described her as “just another Black girl that no one paid attention to [who] loved to get in the conga

and dance.” Moreover, a young Lupe was inspired to sing after seeing a TV performance by Edith Piaf. Despite clearly being attracted to music at a young age, however, Lupe’s parents insisted that their daughter pursue a more stable profession—that of a schoolteacher—and she followed their wishes, though her burgeoning passion was difficult to resist, particularly after the family moved north to Havana when La Lupe was a teenager, where she would study by day and begin to sing by night.After Lupe won a contest singing like the well-known Cuban bolero singer Olga Guil- lot, Guillot encouraged her to cultivate her own style, which she set out to do amidst Havana’s sea of nightclubs. “La Lupe’s Havana, [from 1957 to ’60] had the biggest night life in the world,” says Cuban musicologist Helio Orovio in Troyano’s film.

“Lupe was a phenomenon of the times, and it was a crazy time… La Lupe absorbed all of that and threw it back out.” Indeed, pre-Castro Havana’s nocturnal party scene was infamous for its creativity and excess, and La Lupe soon found herself a part of a trio called Tropicuba, a group that would give the singer her first taste of professional popularity, as well as her first husband. After her husband cheated with Tropicuba’s other member, the turbulent marriage—and the group—would not last and would mark the beginning of a serial run of abusive relationships for La Lupe, relationships many believed would fuel her fiery onstage persona throughout her career. So Lupe embarked on her own, landing a gig at a club called La Red, and built a steady following performing seven shows a night for $28 a week. “She did things, and if the audience liked it, then she’d repeat it,” her pianist at that time, Homero Balboa, recalled in Troyano’s documentary. “If she’d hit me on the head with a shoe and they laughed, she’d hit me every day… At that time, we had the hippies and the existential- ists. It was an audience that was receptive to her immediately. People who wore their shirts backwards, that was her audience.” Her fellow musicians weren’t the only ones taking such abuse, however, as La Lupe would pull her own hair, bite herself, and flail across the stage. “She used to tear her dress. She took her breast out of her dress and banged it against the microphone,” remembered one La Red patron in a 1969 New York magazine article. “She was very feminine and macho all at once—aggressive, irreverent,” adds musicologist Orovio in Troyano’s film. “She was a kind of anticipated rapper… She’d talk, scream, she’d hit the wall, and the music kept going.

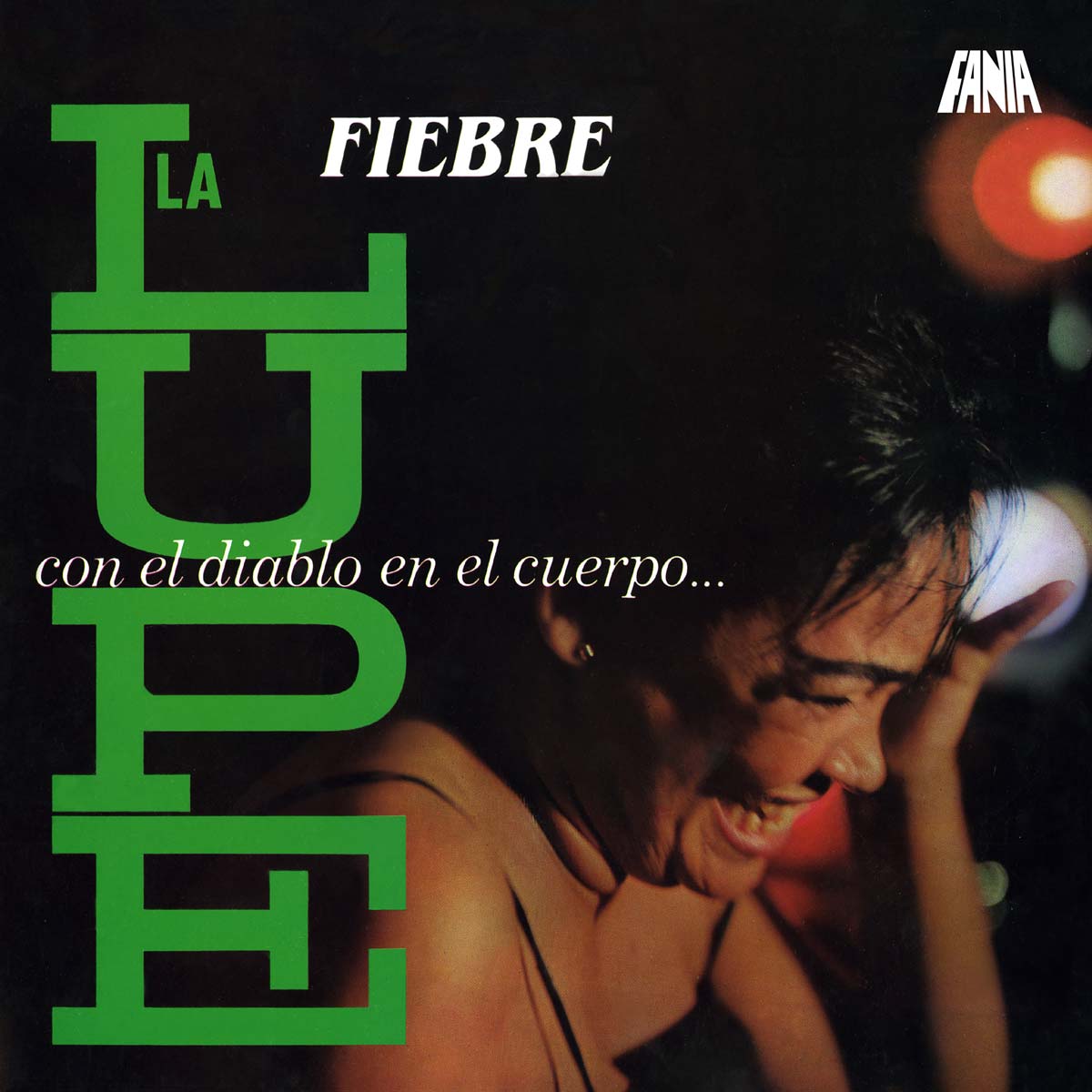

The music went one way, and she’d go another. But all that incoherence would click.” In 1960, it would click enough for the then twenty-year-old (or twenty-three) to land a record deal with the RCA affiliate Discuba Records. The two LPs, Con el Diablo en el Cuerpo (“With the Devil in the Body”) and La Lupe Is Back, would more or less establish the musical blueprint she’d stick to throughout her Spanglish-ized singing career, mash- ing extravagantly arranged pop standards like “Fever” (“Fiebre”) with raw indigenous jams. And though her debut LP was presumably named after the ecstatic Julio Gutiérrez- penned title track and not (necessarily) after La Lupe’s own penchant for onstage “pos- session,” a purchasing public couldn’t be faulted if, after taking one look at the album’s front and back images of a woman clearly transfixed, they thought perhaps the Devil lurked somewhere within the vinyl’s grooves. But just as Lupe was starting to revolution- ize what a female (let alone a Black) singer could do, her rising star was eclipsed by an even more ascendant force, one deemed by some the ultimate savior, and others, the ultimate diablo. “[Fidel Castro] says I was taking attention away from his revolution, and he says I must leave,” Lupe told Rolling Stone in 1972. “When you have a revolution, you cannot afford to have someone like [Beny Moré] or myself around. We take all attention away from it. I’m for everybody, I’m not limited by revolutions, I’m for everybody that got soul!” Thus, in 1962, Lupe took her soul northward, first to Mexico, then Miami, then headed for the Big Apple, where she unceremoniously found herself scraping for gigs along with every other wannabe looking for that big break. Fortunately for Lupe, her big break came via a fellow expat known for creating torrid breakbeats with his hands.

“She was famous in Cuba, but that didn’t matter here,” the late, great Mongo Santamaria recalled in Troyano’s documentary. “She had nothing, nothing, nothing. Wherever I went, she came with me; she knew the songs I was playing. There’s a part in ‘Watermelon Man’ where she screamed and did those jokes of hers. The promoter says, ‘Mongo, if this woman is going to keep going, let’s put a mic on her.’ I said, ‘I’m not kicking her out. Put a mic on her.’” Hence, within a short amount of time, La Lupe had not only found herself a popular band, but had found her ecstatic voice on Mongo’s biggest career hit, a boogaloo-driven cover of Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man,” for Riverside Records, a success that would quickly lead to her own stateside semi-debut, Mongo Intro- duces La Lupe. Released just before Riverside would go bankrupt, its mix of mostly instrumental Latin jazz and Lupe’s peripheral vocals was a soft introduction at best. Nonetheless, it got her picture and name on an LP cover and gave an excuse to tour. “When ‘Watermelon Man’ was hot, we toured the Black theater circuit, starting with the Apollo, and Lupe came along,” recalls Marty Sheller, then a young trumpet player and nascent arranger for Mongo’s band. “Mongo was always extremely popular in New York, and at the Apollo, we’d do a couple of numbers then bring out La Lupe. Now she got so involved, so feverish, that she would bite the side of her hands and hit herself. And when it started to get hot and Mongo would get into his solo, she would stand fifteen yards away and come running, fall down on her knees, and slide right up to the drum while he was playing away. The people loved it! Now, the guys who worked as stagehands at the Apollo had seen so much that nothing much rattled them anymore—she rattled them! The last number she would do was ‘Afro Blue,’ and Mongo’d be playing a solo, and she was in a trance, going crazy, and then she would go stomping off to the side of the stage and the stagehands would hold the curtain back, and you could hear them say, ‘Here comes that crazy bitch! Look out, she’ll hit you!’”

Such raw antics served to increase the buzz surrounding La Lupe, enough so that other Latin luminaries began to take notice. “Mongo wanted to really get out of the cuchifrito circuit,” Sheller explains. “So he started to do more jazz gigs, and La Lupe wasn’t really for that kind of thing. She was really starting to get popular. That’s when she hooked up with Puente, and her career went sky-high.” Mongo, who had once been a longtime per- cussive prince in El Rey del Timbal’s orchestra, encouraged Lupe to go. Ironically, Puente had been one of the early doubters of La Lupe’s talent, yet now here he was courting her. “When I first heard her with Mongo, I didn’t go for her style,” Puente told Rolling Stone in 1972. “She called it soul, but I called it screaming. Then one day, I heard this record that Lupe had done, and I was impressed. I thought it might be good to try to work with her, to see if I could develop her. I was the one who got her to sing the first bolero she ever did, ‘Que Te Pedí,’ and it became her first big success.” Tucked away in the middle of side B of Tito and Lupe’s masterful 1965 debut collaboration, Tito Puente Swings – The Exciting Lupe Sings, “Que Te Pedí” was indeed a slow burner, one of three boleros mixed in with Puente’s finely orchestrated signature rumble. Under the guidance of Tico Records’ roster of heavyweight producers, it would become just one of many iconic songs the duo would spawn over a span of the next two years and five LPs. The shine Puente provided was more than enough to catapult Lupe (now a mother) into Latin music’s limelight, capturing the vocal rapture Lupe had been unleashing in front of crowds throughout the previous decade, and refining it with his veteran touch. Not that recording La Lupe, be it a bolero, rumba, or guaguancó, was a breeze. “She was hell on wheels,” says veteran crooner Willie Torres, who provided many a coro for now-classic Tico sessions throughout the ’60s, including Lupe’s. “She always stood everybody on end.” Longtime engineer and producer Fred Weinberg recalled in Troyano’s film the con- stant challenge of capturing Lupe in the studio. “She was like a hurricane coming through the door. I don’t think no two takes with Lupe were the same, so we would grab what we could. She didn’t care if she popped on the microphone or not; [it would] drive Puente crazy. ‘Soy yo!’ she’d say.” “Puente became a mentor to La Lupe,” wrote historian Joe Conzo in a 2004 Times Herald-Record article. “He provided her with an atmosphere where she could express her creativity.” As much as Lupe benefited from Puente’s craft and name, however, he also reaped from Lupe’s shooting star, one that was perhaps now burning too brightly for El Rey’s ego. “She was a singer with the Tito Puente orchestra, and that’s the way Puente liked to have things,” recalled legendary album designer and Latin music personality Izzy Sanabria in Troyano’s documentary. “But when people were coming to see La Lupe backed by the Tito Puente orchestra…that did not sit very well with Tito.

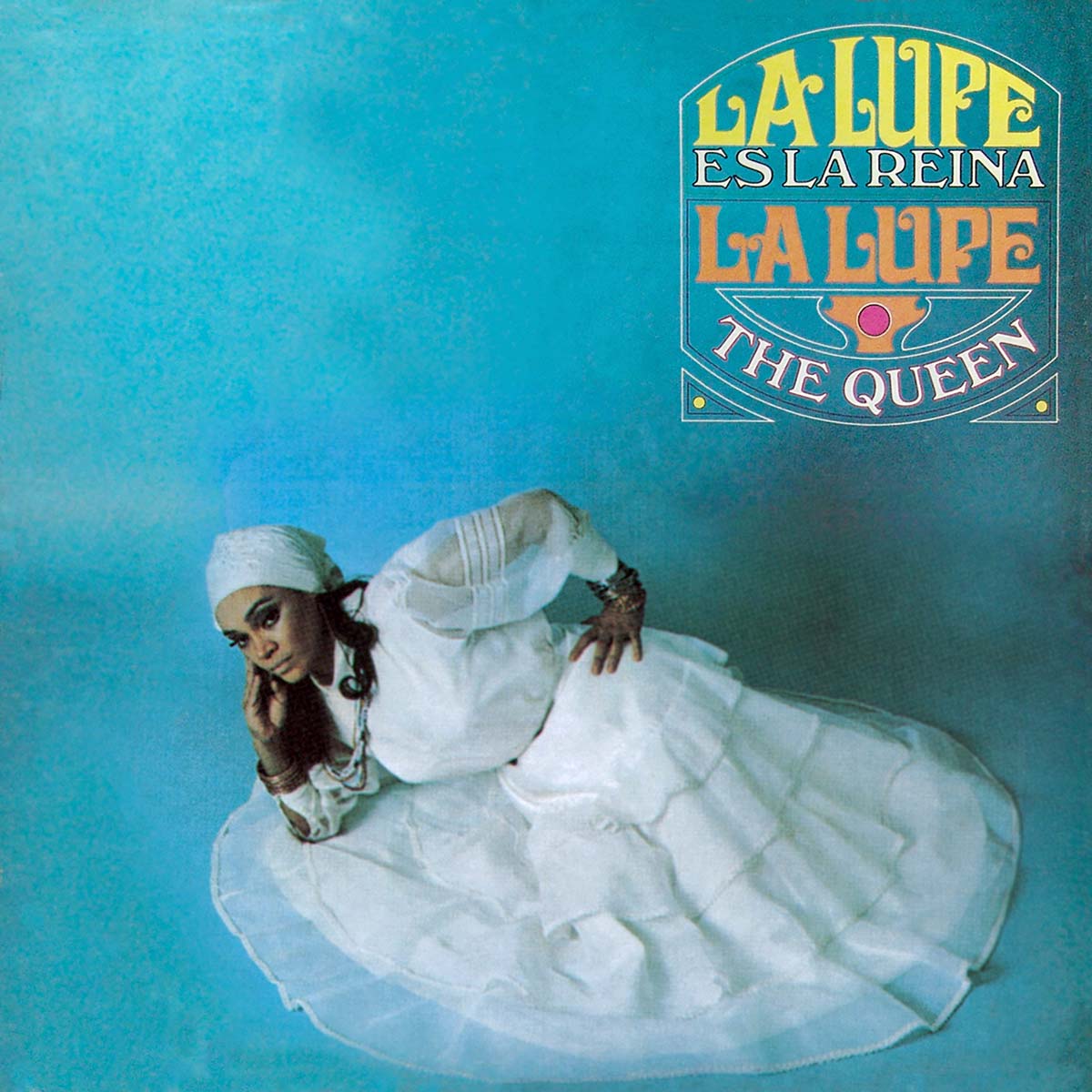

She was too much of a star… No Latino entertainer at that time in this genre of music had gotten that kind of exposure.” Hence, Tito showed Lupe the door. Fortunately for her, Morris Levy, Tico Records’ owner, loved both her talent and the money he was making off of her enough to make her a solo act. La Lupe quickly set out to prove to her former boss (and any other doubter) that she was more than able to sell records on her own. The fact that Puente had essentially replaced Lupe with expat compatriot Celia Cruz had to have added fuel to Lupe’s ire, which she vented in lyrics such as, “I gave everything to my little boss Puente / He left with the girl next door and left me all alone / [coro] Tito Puente kicked her out / He threw me out, he threw me out!” Instead of going head-to-head with Celia, however, La Lupe flexed her dynamic muscles, throwing a stylistic curveball for her first solo LP, Y Su Alma Venezolana, and forgoing big band orchestrations for a pared-down acoustic set of catchy Venezuelan numbers. “La Lupe was my favorite,” Izzy Sanabria says from his home in Tampa, Florida. “The difference between Celia and her is that Celia was a lady—great style, great voice. But La Lupe sang from deep within her soul. No other way I can explain it.” From 1966 to 1974, Lupe’s soul would indeed be in full force on a dozen LPs, a run that could have been christened—after her ’68 LP of the same name—La Lupe’s Era. She had become a bankable star on her own charismatic terms, becoming in 1969 the first Latina to headline Carnegie Hall, and commanding up to $10,000 a night. “People like me because I am honest,” La Lupe told New York magazine in 1969. “You can hear my records in all the houses in el barrio. I pray to God that I never lose my honesty.”

In addition to selling millions of records, she was invited to play rock festivals with the likes of Iron Butterfly, Jethro Tull, the Supremes, and Ray Charles, angling to appeal to the psychedelic pop crowd, a crowd she hoped might buy her Queen Does Her Own Thing LP, the Harvey Averne–produced, Marty Sheller–arranged take on rock and soul hits. The Village Voice took notice, virtually exclaiming, “She is Janis, Aretha, and Edith Piaf tied into one. She sings ballads like Piaf-plus, and up-tempos like the other two—plus madness… She could make a fortune on the rock scene… La Lupe—she’s devastating, and she seems to be devastating herself… Jim Morrison take note.” Morrison wasn’t around long enough to take note, but TV host Dick Cavett certainly was. “When she got the call to do Dick Cavett,” recalls Marty Sheller, “Lupe said, ‘Marty, I want you to do an arrangement of “Afro Blue” for me.’ Bobby Rosengarden led [the show’s] big band, and Victor Paz was lead trumpet. Now, most American musicians have never played a Latin style 6/8, so it took a few times to get it right. Even though it was rehearsal, Lupe started going into her zone, and the musicians were crackin’ up; they had never seen anything like this. But it was all sounding very good. So it came time to tape the show and she came out. I said, ‘Holy crap, look at what she’s got on!’” “Wow was on many lips,” Cavett recalled of the episode in Troyano’s film, comparing La Lupe’s energetic presence to that of Jimi Hendrix and Fred Astaire. “The audience knew they were onto something different than anything they’d ever seen.”

By the time Lupe’d finished her frenetic version of “Afro Blue,” the national television audience had seen more of her popping curves and gold uni-suit than perhaps they had wanted to, not to mention Dick Cavett’s half-naked body dancing beside her. Meanwhile, around the same time La Lupe was causing controversy on mainstream television, Fania Records and their marquee act, the Fania All-Stars, were making a big splash in the Latin market with music they were branding as salsa, and inciting near riots at sold-out venues such as Yankee Stadium. It was a hip, young, more brash Nuyorican spin on Afro-Cuban music that was beginning to revolutionize the Latin music scene in the Big Apple and beyond, and showcased many songs written by Tite Curet Alonso, who had gotten his big break with his first hit, “La Gran Tirana,” on La Lupe’s Queen of Latin Soul years earlier. Though their fiery energies would’ve seemed a natural match, Fania wanted little to do with La Lupe, having already signed their lone significant female act, Celia Cruz, whom they would eventually don the “Queen of Salsa.” For her part, the older Celia seemed to respect her peer. “Lupe is a good interpreter of songs in modern music,” she told Rolling Stone in 1972. “It is not my style, but she is a creator too, and I admire her for that.” Hence, La Lupe’s only all-star turn would come on “Sale el Sol” in 1974 at Carnegie Hall, as part of the Tico-Alegre All-Stars concert, the curtain call for Morris Levy’s fading Latin empire, which would soon be absorbed by Fania’s rapid expanse. And though she continued to release solid product throughout the remainder of the ’70s, La Lupe’s shine began to wane. The 1980s were downright cruel, as rumored drug addiction, money woes, an apartment fire, and a debilitating fall severely stressed the mother of two, forcing her to rely on the mercy of homeless shelters, welfare checks, and fellow musicians.

Knowing that the music inside of her wouldn’t let go, she let go of the music, giving up secular performances altogether, while trading in her Santeria beliefs for those Pentecostal. In 1992, when she died in her sleep of a massive heart attack at the age of fifty-six (or fifty-nine), many gathered to mourn one of the greatest performers they had ever seen or heard. And though she had accomplished more than most, there still lingered a feeling that perhaps the controversial icon had failed to reach her God-given potential. She had been a fighter all her life, overcoming racial, political, and personal obstacles along the way. “I’m Black and Cuban, a lot of people don’t like me for this,” she had told Rolling Stone twenty years before her death. “They prejudiced because you Black, they prejudiced because you are fat… There was prejudice in Cuba, but I don’t care. There was prejudice in America when I came here too. I’m still fighting for La Lupe, I’m still fighting… I do soul music because I like it. I’d sing in China as long as the people got soul!”

“In Cuba, they called me crazy,” La Lupe would later say. “They didn’t understand me.” The Bronx—where today you’ll find La Lupe Way—most definitely did.