“I think people like me,” the legendary La Lupe, one of the most electrifyingly memorable performers to ever blitz Planet Earth, once said in an interview, “because I do what they’d like to, but can’t get free enough to do.” True, some would say La Yi Yi Yi was free spirit incarnate; others would say she was simply possessed. Literally. No surprise, given the voluptuous vocalist’s onstage inclination to bounce off walls, rip her clothes off, throw shoes at her band, and claw, bite, and scratch herself, all the while belting a tune with orgasmic zest. Such musical drama reportedly drew international celebs like Marlon Brando, Ernest Hemingway, Simone De Beauvoir, and Jean Paul Sartre into her court. But it was also such anything-can-happen antics, along with new leader Castro’s bent on nationalizing and cleaning up Havana’s infamous nightclub scene, that eventually landed La Lupe in New York City where, from 1962 until her untimely death thirty years later, she would experience the ultimate highs and lows of life in a business that would crown her the Queen of Latin Soul yet watch idly as she died a pauper’s death.

La Lupe was born Guadalupe Victoria Yoli Raymond in San Pedrito, a town in the southern part of Cuba near Santiago de Cuba. (There seems to be an agreement about the day of La Lupe’s birth: December 23. However, the actual year of her birth appears to be up for debate. Most sources say either 1936 or 1939. Archival footage from La Lupe’s funeral shows 1936 as the date given on her casket, while La Lupe’s tombstone at St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx gives her birth year as 1939.) So rural was her hometown that she later remarked, “I was born in such a small town, nobody knew about it until I left.” Though attracted to music at an early age, Lupe’s parents encouraged their daughter to pursue a more stable profession—that of a schoolteacher—and though she followed their wishes, she couldn’t resist her passion for music, particularly after the family moved to Havana when La Lupe was a teenager. A melting pot of Eartha Kitt, Edith Piaf, Olga Guillot, and Nina Simone, the singer’s tempestuously elastic voice could both coddle and torch any genre. Whether interpreting boleros or son montunos, pop schlock or rock-and-roll ditties, jazz standards or Broadway show tunes, La Lupe simply couldn’t contain the music within herself. And no one—be it Mongo Santamaria, Tito Puente, Dick Cavett, or the Fania All-Stars—could ever, no matter how hard they tried, contain her. “I’ll never forget the first time I met La Lupe,” says Harlemite Henry “Pucho” Brown, himself the crowned Latin Soul Brother and founding bandleader of Pucho and his Latin Soul Brothers. “I went to visit Marty Sheller, who was the musical arranger for Mongo at the time. He was living on 86th Street and Broadway, in a building where there were a bunch of musicians. I walk in, and there’s this broad laying on the couch, all dirty feet and not lookin’ like much—and it was Lupe.

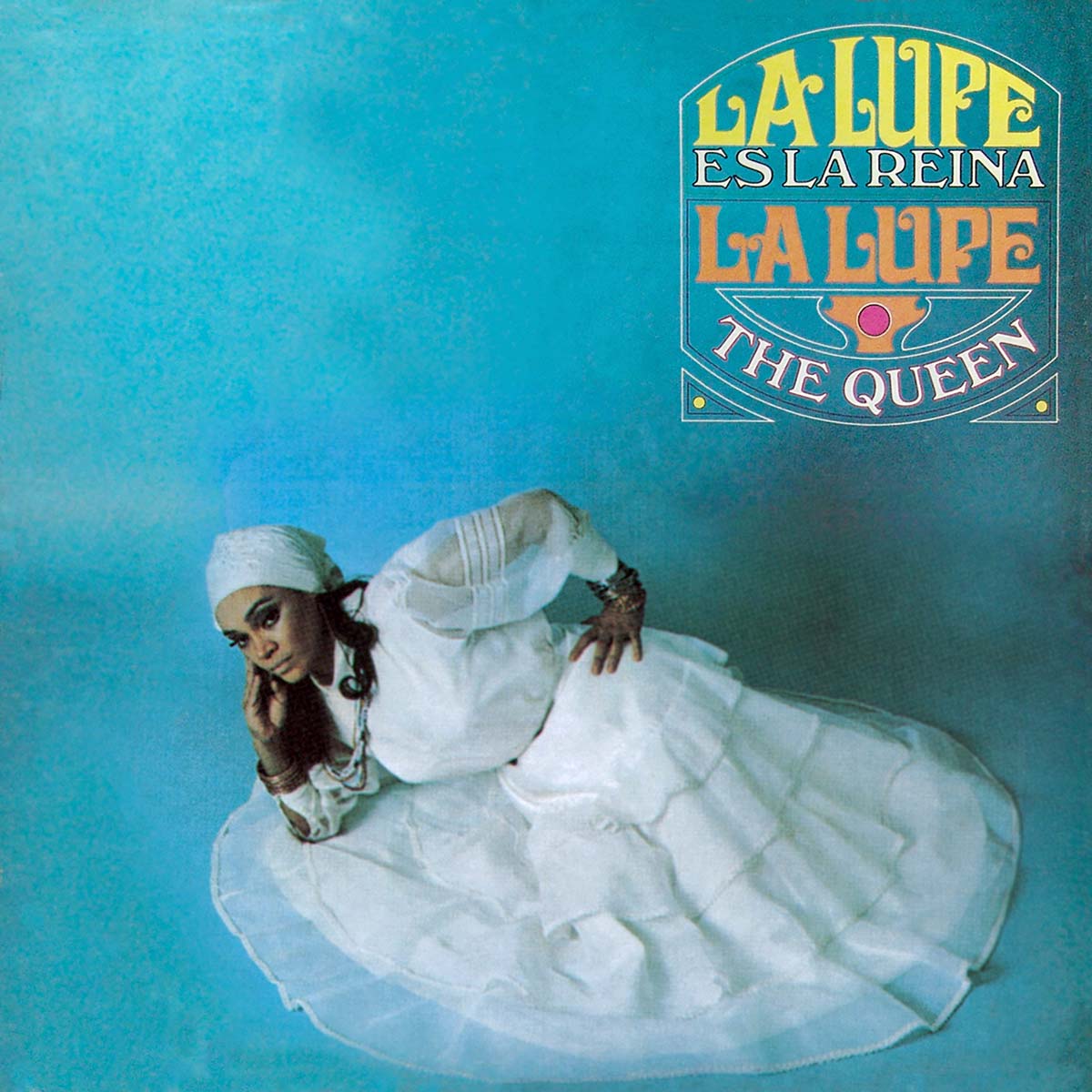

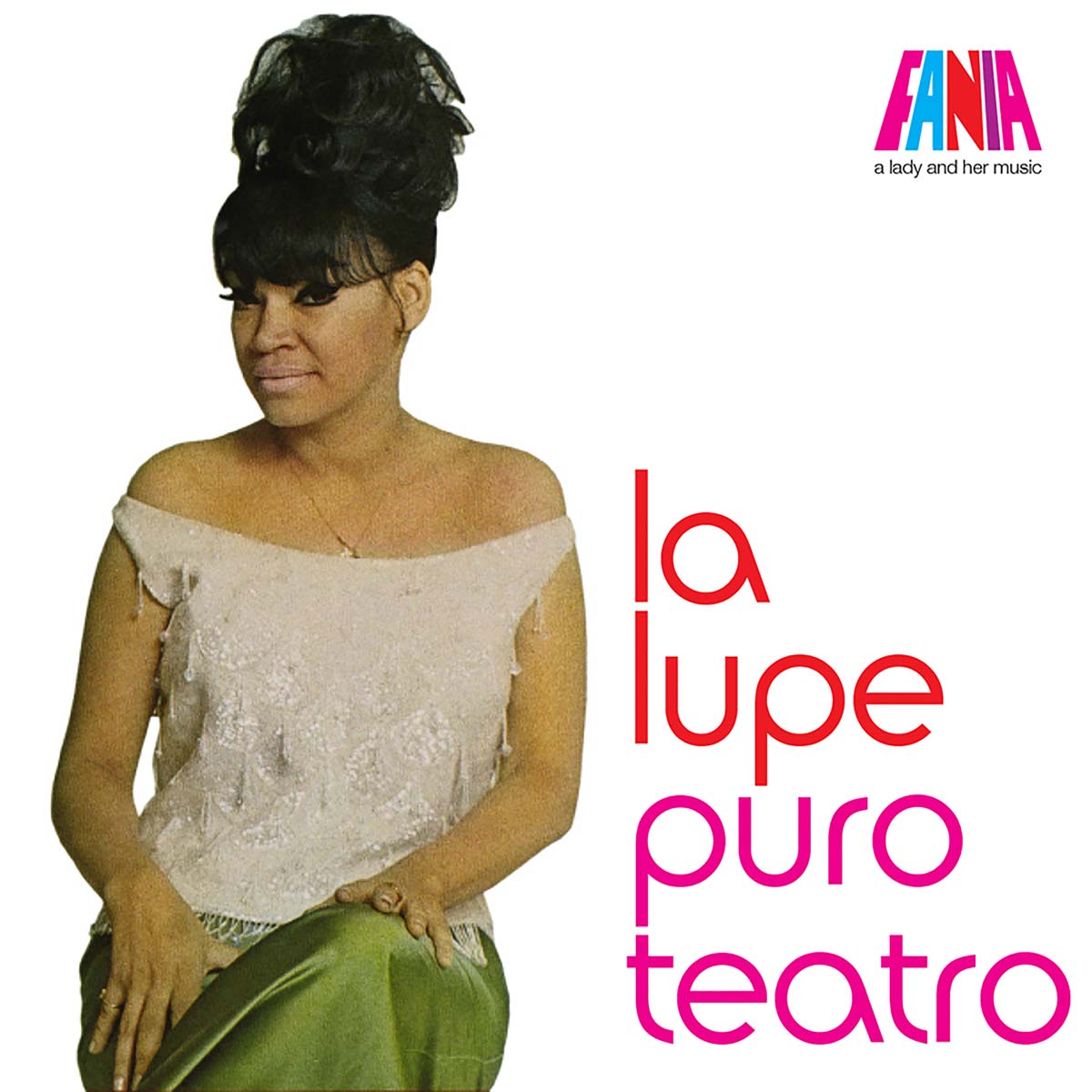

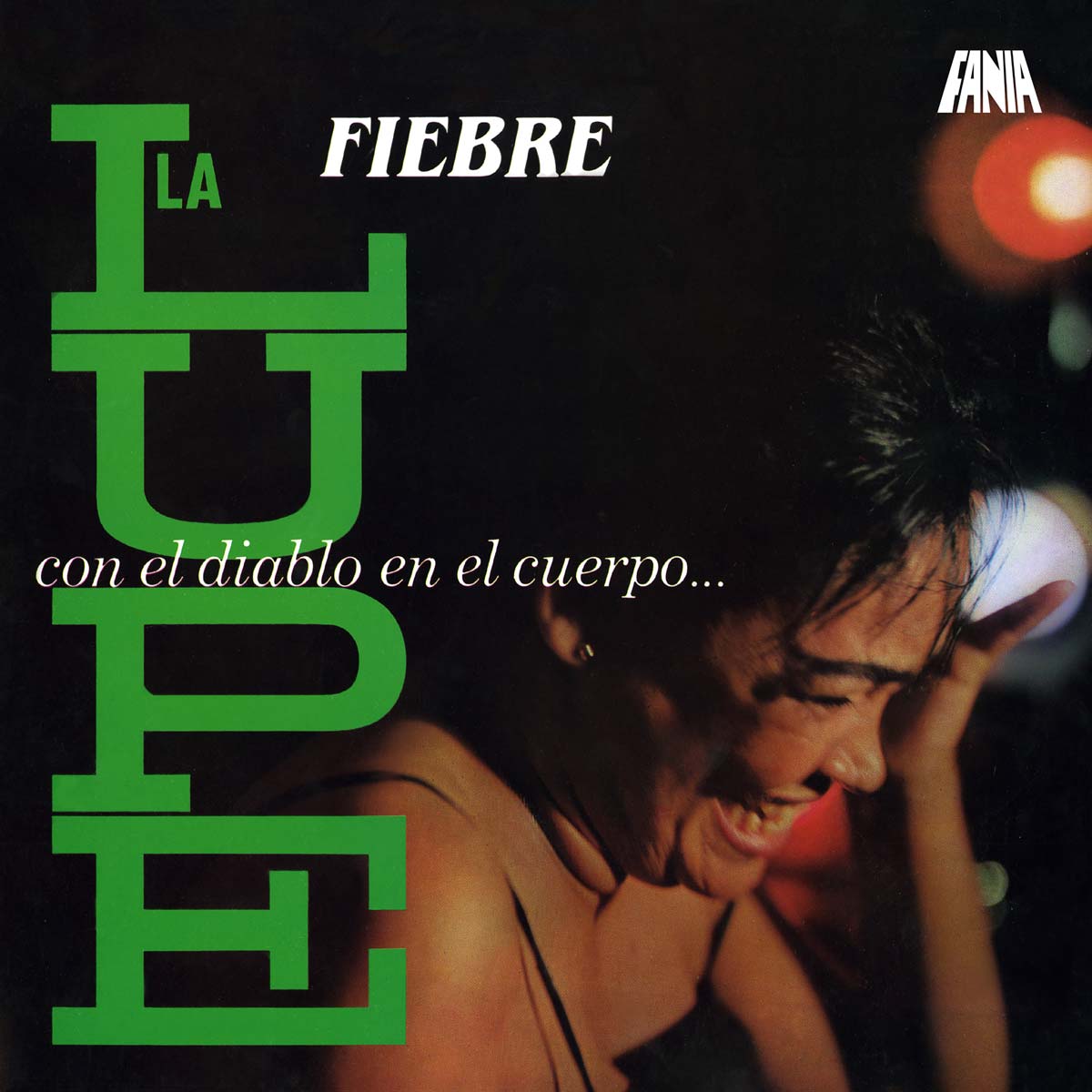

This was around 1962. Then the next thing I know, she’s a big star! When I saw her perform at the Apollo with Mongo, she was great—a little wacky, but she was great, with a lot of fire! And she liked that voodoo s***.” That “voodoo s***” was actually Santeria, and for much of her life, La Lupe was indeed known to be a Santera. Some folks thought that her religious practice could be heard throughout the dozens of LPs she would eventually make, beginning with her first full-length effort you hold here—Con el Diablo en el Cuerpo (“With the Devil in the Body”). Recorded April 1960 in Havana, likely at Radio Progreso, and released for the RCA affiliate Discuba Records the following year, the then twentyyear- old (or twenty-three) wunderkind follows the musical blueprint she’d stick to throughout her Spanglish-ized singing career, mashing extravagantly arranged pop standards with raw indigenous jams. Con el Diablo en el Cuerpo was presumably named after the ecstatic Julio Gutierrez–penned title track and not (necessarily) after La Lupe’s own penchant for onstage “possession.” However, a purchasing public couldn’t be faulted if, after taking one look at the album’s front and back images of a woman clearly transfixed, they thought perhaps the Devil lurked somewhere within the vinyl’s grooves.

Maybe it was the type of controversy Discuba’s record execs were seeking at the time. Regardless, from the get-go, La Lupe turns each song into a full-fledged drama, wringing histrionic heartache even from white-bread teen superstar Paul Anka’s two included numbers, “Crazy Love” and “So It’s Goodbye.” Of course, it doesn’t hurt to have a top-notch orchestra backing you, and La Lupe has just that, alternately led and arranged by pianist Felipe Dulzaides and multi-instrumentalist/studio veteran Eddie Gaytan, whose musicians La Lupe teasingly encourages during their choruses and solos with shouts of “¡Qué lindo!” and “¡Háblale, háblale!” Moreover, La Lupe raises the already high bar on the Eddie Cooley/Otis Blackwell standard “Fiebre” (“Fever”), a ubiquitous tune she would obliterate again later in the decade for Tico Records. We’ll probably never know whether La Lupe thought Con el Diablo en el Cuerpo was going to be the beginning of a long recording career in Cuba, but the fact is, after her follow-up Discuba release La Lupe Is Back, she’d never make another record in her native country. Soon after the sophomore release, she’d find herself in New York City, dominating the ’60s like no other female Latin singer, packing venues from the Palladium to Carnegie Hall, well on her way to becoming a controversial icon, even after being supplanted by her compatriot, the soon-to-be-crowned Queen of Salsa, Celia Cruz. “In Cuba, they called me crazy,” La Lupe would later say. “They didn’t understand me.” The Bronx—where today you’ll find La Lupe Way—eventually did. La Lupe did indeed become a teacher, one of music and drama. Con el Diablo en el Cuerpo is the first lesson.

Liner notes by Matt Rogers