Raymond Barretto Pagan was born to Puerto Rican parents in New York on April 29, 1929. When he was barely four years old, his father decided to leave home and return to Puerto Rico. His mother settled in the South Bronx and raised her three children by herself. From an early age, Barretto was influenced by two styles of music: Latin and Jazz. During the day, his mother listened to the music of Daniel Santos, Bobby Capó, and the Los Panchos Trio. However, as Ray grew up, he fell in love with Machito Grillo, Marcelino Guerra, Arsenio Rodríguez, and the Jazz orchestra greats he heard on the radio; stars like Benny Goodman and Duke Ellington.

When he turned 17, Barretto enlisted in the United States Army and was sent off to World War II. While stationed in Germany, he heard the song that changed his life: “Manteca” by Chano Pozo and the Dizzy Gillespie band. When he left the army, Barretto returned to New York and, influenced by the percussion instruments that his idol Chano Pozo dominated, he bought a bongo. But he wasn’t satisfied with the sound, so he went out and spent 50 dollars on some tumbadors he saw for sale in a local neighborhood bakery. And that’s how he took his first steps onto the nightclub music scene. His first recording was in 1953, with Eddie Bonnemere’s Latin Jazz group at the Red Garter lounge in New York. In contrast to famous conga players of the time like Cándido Camero, Mongo Santamaría, and Patato Valdés –who started out with Afro-Caribbean rhythms and worked their their way up to Jazz– Barretto started out in the world of Jazz; it would be years before he would make a foray into other Latin rhythms. On one occasion, percussionist Monchito Muñoz invited Barretto to an audition with the José Curbelo Orchestra. He stayed for four years.

This experience helped him develop his talent for Latin dance music. He worked with the group on the album “Wine, Woman y Cha Cha Cha” in 1955. At the same time, his knowledge of Jazz allowed him to work with various bands of the time, such as Max Roach, Charlie Parker, Art Blakey, Herbie Man, Dizzy Gillespie and Cal Tjader. In late 1961, the opportunity presented itself to record an album with Riverside Records, owned by Orrin Keepnevo, who was trying to build a catalogue of Latin music. It was Keepnevo who suggested Barretto form a band to record with. Thus was born La Charanga Moderna. With La Charanga Moderna, Barretto altered the instrumental format of traditional charangas in a radical move by incorporating trumpet and trombone. In 1962, he made his presence on the music scene known with the album “Pachanga with Barretto.” On the heels of this album’s success came “Latino” in 1963. He then joined Tico Records, where he recorded the album “Charanga Moderna,” which produced the hit “El Watusi.” This number was the midas touch; his first album went gold, selling more than a million copies. It also earned him a place in the US market. “El Watusi” became the first Latin song to make the Billboard charts. Barretto continued to record with Tico Records until he decided to join a new label, United Artist Records.

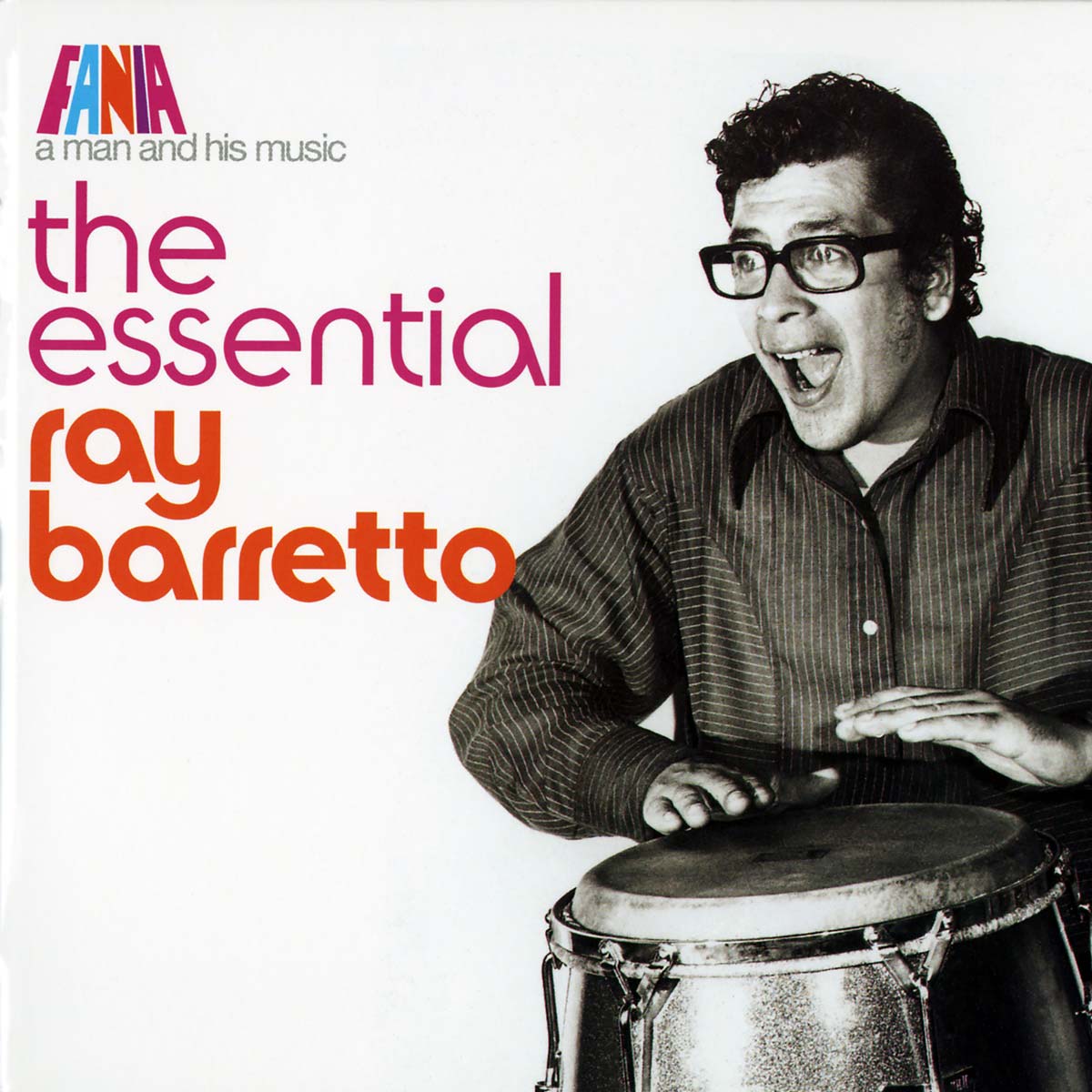

There, he was able to achieve a new sound, a West Indian sound closer to the style of the bands of the time, one that combined violin with trumpet and trombone. His first album with the label was “El Ray Criollo” in 1966, followed by “Señor 007” in 1969. The latter did not meet the artist’s own expectations. He followed these up with “Latino Con Soul” and “Viva Watusi,” collaborating with Adalberto Santiago on both. Barretto’s future would change course in 1967, the year he would sign with Fania Records, creating at that very moment the sound of the Ray Barretto Orchestra. His first album on the label was “Acid,” with the collaboration of Adalberto Santiago and Pete Bonet. He then recorded “Hard Hands,” “Together,” “Power,” “The Message,” and “Que Viva La Música.” Barretto was dealt a serious blow in 1972 when five of his best musicians left the orchestra to form the band Típica 73: Adalberto Santiago, Orestes Vilató, Johnny “Dandy” Rodríguez, René López, and Dave Pérez. On the spot, Barretto stopped making Salsa music to record the album “The Other Road,” which took him back to his Jazz roots. It wasn’t long, however, before Barretto returned to Salsa, with the album “Indestructible” and the voice of Roberto Romero –better known as Tito Allen– who replaced Adalberto Santiago. Tito Allen worked only briefly with “The King with the Firm Hand,” and was then replaced by Tito Gómez, who later accompanied Rubén Blades on the album “Barretto” in 1975. Immediately following this recording he made several Latin Jazz albums, and then reunited with Adalberto Santiago in 1979 to make the album “Rican/Struction.” A year later he made the album “Fuerza Gigante,” with vocals by Ray de la Paz and Eddie Temporal. This was followed by “Rhythm of Life,” released in 1982. In 1983, he produced the classic album “Tremendo Trío” with the collaboration of Celia Cruz and Adalberto Santiago.

The album “Todo Se Va A Poder” was the next project for the Salsa musician, with vocals by Cali Alemán and Ray Sabaá. Tite Curet Alonso contributed the composition “Aquí Se Puede,” and the Ray Barretto Orchestra kept churning out the hits. In 1988, Barretto won a Grammy for the album “Ritmo En El Corazón,” with vocals by Celia Cruz. Storming onto the romantic Salsa scene that dominated the late 80s, Barretto made the album “Irresistible” in 1989. Later, with the production of the album “Soy Dichoso” in 1992, he ended his professional relationship with Fania Records. However, Barretto remained active on the music scene, hovering between Jazz and Salsa without ever losing his innovative spirit. Ray Barretto A legend in the world of Salsa and Latin Jazz. Manny Oquendo (Percussion): “The first time I met him was when we were recording with the Cuban flute player Lou Pérez. I was playing the timbal and Ray was playing the conga. I remember he was playing it with a Jazzy kind of style, and I told him not to play it that way, because we were doing a traditional Latin number. Ray and I have a lot in common. We were both born in Brooklyn, we both had two marriages, we both worked with José Curbelo and Tito Puente (but not together). When he was playing with his brass band, I was playing with Johnny Pacheco and his brass band. We socialized a lot, because the producers took advantage of the musical rivalry between his orchestra and Eddie Palmieri’s. We always had a lot of mutual respect.” Johnny “Dandy” Rodríguez: (Percussion): “When my father, Johnny ‘La Vaca’ Rodríguez, passed away, Ray went to the funeral. And I remember him telling me that when he first started out he got a lot of criticism and people called him “The White Mongo” because his style was very similar to Mongo Santamaría. My father gave him advice and support. He told him that he believed in him, and to just forget about it. Ray and I didn’t talk for many years because of what happened with Típica 73, but one day I ran into him in the bathroom at the Casa Blanca Club, and that’s when we started talking again. Later I recorded a Jazz album with him. I’ll always remember him as an intelligent musician ahead of his time.” Eddie Montalvo (Percussion): “I was going to see him at the Hunt’s Point Palace. I never dreamed I would ever meet him. One night he was playing a dance with Tony Pabón’s orchestra, and we switched with his orchestra in Boston.

I remember that Johnny Rodríguez invited me to play the second conga on the song “Que Viva La Música,” with Johnny on the tumbador and Ray on the quinto. Barretto liked the way I played the tumbador. We worked together for a long time with the Fania All Stars. I always thought of him as my idol. I’ll never forget how when it was his turn to play at shows, he would say that I was just keeping his seat warm for him…” Andy González (Bass): “Barretto saw me playing with Monguito Santamaría the night they recorded the album “Fania All Stars at the Red Garter” and he asked me if I wanted to join his band. I didn’t give him an answer right then and there; I thought about it for four months before I said yes. I joined the group and we immediately recorded “Together” and then went to Venezuela. I remember we had two uniforms – one of them was a white tuxedo with a red shirt and a black sash. Well, it turned out that the night we were performing for the first time, at a dance in El Corso, the waiters had the exact same uniforms we did, and people kept confusing us and asking us for drinks. I also remember at one dance, while we were playing “La Hipocresía Y La Falsedad,” some guy shot another guy in the face, and people started rioting, and the promoter told us to just keep playing. We all got our instruments and got out of there. Ray always visited me at my house and we would listen to music. I visited him, too. The last time I played with him was at a Chico O’Farrill’s big band concert. He came up and did a number with us.” Jimmy Sabater (Vocals and Percussion): “I sang a lot of choruses with him on his first few albums with Fania Records. He played with me on my album ‘Solo.’ We were always friends, and I’m going to miss him a lot. Johnny Colón (Conductor and Musician): “When I started out with my orchestra, I switched with him at the Hot Point Palace. I’ll always remember him for being so attentive to his fans. He did everything for them; he never denied them any encores. He was a very intelligent musician and always thought about his family.” Gilberto “El Pulpo” Colón: (Piano) “I met Ray through Oscar Hernández. Every now and then Oscar couldn’t make it, so I would fill in. When Oscar left the band to go play with Rubén Blades, I joined Ray’s orchestra. Around that time Ray was always singing about La Paz. I was in Ray’s orchestra because Héctor Lavoe was in rehab and when Héctor got out, I left the Barretto Orchestra. Ray was upset, and told me that if I stayed, I would make more progress. He was right. But I was doing other things.” Ralph Irrizary: (Percussion) “I remember I was there when the Fania All Stars were recording ‘Our Latin Thing.’ I was 16 years old. I had always been a huge fan of the Barretto group, ever since I had become a musician. I met Ray one day when I was playing at the Corso. The club manager had been talking to Ray about me, because he knew Ray was looking for a timbal player. That day, Ray was going to come watch me and I was really nervous. We did the first set, and then the second, and Ray still wasn’t there. During the last number I always did a solo, and when I finished, I saw Ray standing there in the crowd, shaking snow off his coat. When the song ended, he told me he was going to give me a call to talk about rehearsing with his orchestra. Three months or so went by, and then he called.

I thought he had forgotten about me, but he called and told me rehearsals were starting the next day and he was expecting me. I recorded with him on the album ‘Rican/Struction’ and not long after that we were going to be playing at Madison Square Garden. I had another job at the time, and I had to ask my boss for permission to go on a three-week tour of Venezuela. He told me no, and I was forced to resign. I’ve been a full-time musician ever since. I’ve been playing professionally for 26 straight years, and I owe it all to Ray Barretto. Orestes Vilató: (Percussion) “I started with Ray when he was playing the charanga. The charanga was losing steam, but the idea of adding a trumpet and a trombone was very successful. In my opinion, this idea reverberated in Cuba, because Changuito commented on the new sound. It also influenced bands like Los Van Van, Son 14, and others. In 1966, we won the first Momo de Oro in Venezuela for the song ‘Salsa y Dulzura.’ Ray was a complete musician; he would sit down at the piano to compose and arrange songs. He always said you had to listen to everything. Eddie Palmieri invited me to join his orchestra, and I told him I couldn’t, because I was making a lot of money doing advertising for Ray that he couldn’t do because of his health. Ray learned late how to drive his first car, which was one of those New York taxis. The album ‘Acid’ led me to the band Santana. Barretto was very romantic; he loved the way Graciela sang. He was a child in a man’s body. If I hadn’t met Ray I wouldn‘t have made anything of myself. The last thing he said to me was that he would see me in another world.” Pete Bonet: (Vocals) “I remember we were in Africa on a tour with James Brown, and all of a sudden this French guy came up on stage, took the microphone away from me, and started talking. The bass player understood what the guy was saying, and passed out. When he came to, he said that somebody had killed Martin Luther King and that the United States were burning. Something similar happened when we were on our way to California; we were passing through Texas, and we heard that somebody had killed John F. Kennedy. When we arrived, a three-day mourning period had been declared and we couldn’t play.” Jimmy Bosch: (Trombone) “I started working with Ray in the 80s. He was like a father to me. I remember during performances, when he tried to end the number we were playing, we would just keep on going. He would keep looking at us, trying to say: ‘Either I’m going to kill you, or you’re going to kill me.’ He was an inspiration to all of us. He always told us to better ourselves and learn new things. I hope that the legacy of this Afro-Caribbean musical giant never fades away. Dave Valentín (Flute): “The most intelligent man I have ever know. My best friend and one of the greatest musicians of his time. One time I invited him to play on a two-week tour in Europe. Ray told me it had been 25 years since he’d done that, and he agreed to come. I know he had a lot of fun, because he didn’t have to worry about leading. I gave his son Chris flute lessons.” Goerge Rivera: (Close Friend) “He was a tremendous musician and a real humanitarian. He always participated in benefits. All of his music had a lot of feeling, and a lot of purpose. He dominated the drums, and he was a friend to all. I’m going to miss him a lot.” Ray Barretto WORKIN’ IT “I need just a little more time.” was Ray Barretto’s standard line to Jerry Masucci whenever he asked the conguero about the progress of his recordings. Ray was the consummate perfectionist when it came to his sessions. He would spend hours in the studio during the mixing. He was also the only Fania artist that would insist on being present for the mastering, where the final dimension of sound quality is brought to a record before it is manufactured. By the time Ray was signed to Fania in 1967, he was already a pro in the studio.

Ray developed his musical ear during the 1950’s and 1960’s recording as a sideman for many Jazz artists on the Prestige, Riverside and Blue Note record labels. Working with individuals like Dizzy Gillespie, Oliver Nelson, Art Farmer, and especially the engineer Rudy Van Gelder, Ray received a musical education unlike any he would have gotten formally, including at the prestigious Julliard, where he was discouraged from pursuing a career in music. Ray’s start as a bandleader came as a result of a conversation in 1961 with record producer Orrin Keepnews, who was looking to cash in on the pachanga craze that was beginning to take hold of the New York City club scene. Keepnews was looking to make a connection with either Charlie Palmieri or Johnny Pacheco to record a pachanga album for the Riverside label, a Jazz label back then. When Keepnews approached Ray to see if he could make the introduction, Ray asked to record the pachanga production himself. Keepnews agreed. Ray approached pianist/arranger Hector Rivera, and with his help recorded “Pachanga With Barretto”, the first of two albums on the Riverside label. According to pianist/arranger Alfredo Valdes, Jr., a member of Ray’s band, La Moderna, between January 1962 and December of 1963, the band was formed after the recording started to get airplay. The sound of La Moderna was conceived by Ray, who would assign the task of arranging the music to Alfredo, and pianist/arranger Gil Lopez, who at the time was with Tito Puente’s orchestra. During the two-year period that Alfredo was with the band five albums were recorded, two for Riverside, and three for Tico Records. The band worked out the repertoire at a weekly gig at the Tritons, a Bronx nightclub. When the musicians were comfortable with the new material they would go into the studio and record. Ray arrived at Fania with a new band. The new setup was a conjunto featuring two trumpets and a rhythm section comprised of piano, bass, timbal, and conga, along with two vocalists. The band featured Roberto Rodriguez and Rene Lopez (trumpet), Louie Cruz (piano), Orestes Vilato (timbal), and Adalberto Santiago and Pete Bonet on vocals. The band didn’t have a steady bassist until the arrival of a seventeen year old by the name of Andy Gonzalez, who would make his recording debut on “Together”. Eventually a bongocero would be added to the conjunto, the first being Tony Fuentes, who would later be replaced by John “Dandy” Rodriguez. A third trumpet would also be added later on as the band evolved. It was with this format that Ray would strike gold, both on the bandstand and the recording studio. Getting to that point, and remaining there, was due to his musical vision, and his skills as a bandleader, skills he developed after a long recording career as a sideman in Jazz, as well as with the bands of Jose Curbelo and Tito Puente. The band was always well rehearsed according to pianist/arranger, Louie Cruz. Louie further states that aside from rehearsing at Ray’s New Jersey home, the band would also rehearse any new material at their weekly gigs at venues such as the Corso, a legendary New York City nightclub. As he recalls, the band would arrive early to the gig and start the first set with the new material. The crowd’s reaction would be an indicator Ray would take into consideration when deciding if the tune made it into the band’s book. In Louie’s estimation, the tunes always made it into the band’s book due to Ray’s keen ear and musical vision. Ray had a great ear for music, and was always on top of things where the band was concerned, so much so that when Louie was given a tune to arrange Ray would show up at his home with the tune, and wait until the arrangement was completed the way he wanted it done. This process continued until Ray was completely confident that Louie understood his musical vision. After he was confident with Louie’s skills as an arranger, Louie was left alone. When the band went into the studio to record, it did so only when Ray was sure that they had the repertoire down so tight that they could comfortably perform it with confidence. Most of the tunes recorded for Fania were done with only one take, and very little overdubbing. Jon Fausty, who engineered many of Fania’s productions, recalls that Ray’s bands were always well rehearsed. There was always good communication between the band and Ray, and they fully understood his musical concepts. Jon viewed Ray as a highly educated individual, as well as an educator. He credits him as being instrumental in helping to form his views on how to properly present the rhythm section sonically.

Ray was also very helpful in the studio during the mixing. Jon recalls that he had a grasp on how to modify the balances of his recordings, and would always insist on being present for the mastering with Jack Adelman at RCA studios, something the other artists never bothered with. With every Ray Barretto production, what the listener gets is the very best an artist has to offer, both musically and sonically. That is something that I’m sure you’ll appreciate after listening to this collection that spans over three decades. Written By George Rivera Remembering Ray Barretto Percussionist, Band leader, Composer, NEA Jazz Master & Grammy Award Winner Hard hands, warm heart, Ray Barretto’s legacy remains in the beat of the metronomic clave of Latin New York streets. From el barrio to the boogie down Bronx, from “do or die Bed-Stuy” to as far as France, musical tributes to the Puerto Rican percussionist are blasting from radios from the four corners of the world. Here in Spanish Harlem, the womb of Salsa music -where Rafael Hernandez opened the first Latin music store in 1927– many remember Ray Barretto. I first heard Ray over AM radio when I was about 13. I turned my transistor to Cousin Brucie’s Top Hits Countdown where I heard the sounds of Barretto’s hit, “Watusi” moving my mixed Boricua blood. I didn’t know then that Ray Barretto had already made a name for himself on the Jazz scene. That he had been born of Puerto Rican parents in Brooklyn, raised in El Barrio and then the South Bronx. All I knew was that this music belonged to my ‘hood and here it was on AM radio sandwiched between James Brown and the Beach Boys. We had arrived! His was an aggressive sound with sophisticated swing at a time when Ray’s band was the hottest thing in NYC. You could count on Ray to have the best musicians, creative arrangements and the most danceable of repertoires. When “Indestructible” was released, it stood out by dint of its cover photo fronting Ray as Clark Kent in the process of morphing into Superman. This was not your average corny cover of the time sporting near naked women or a bunch of ugly guys.

This was a cover that related to my Boricua NYC life. Like the real Superman, that cover featured an ordinary man about to give us some extraordinary music that healed our souls while moving our bodies and nurturing our minds towards further horizons. More than 30 years later, that particular tune, “Indestructible,” remains the standard by which all young percussionists are measured. From Oreste Vilato (Santana fame) to Little Ray Romero (Eartha Kitt), Barretto always picked his boys from among the best. And when these two left for greener pastures, Barretto’s remarkable eye for talent fell on Little Jimmy Delgado (now with Belafonte), barely 17 when he debuted with the Barretto band. Later, a twenty two year old Ralph Irrizarry took the timbale chair before blowing up with Ruben Blades and the Mambo Kings movie. In fact, vocalist Ruben Blades had already recorded but it was with the Ray Barretto orchestra that he got his spotlight in New York. Ray Barretto loved Jazz, falling for the conga after hearing Chano Pozo’s recording of “Manteca” with Dizzy Gillespie in 1947. Ironically, it was that same tune of “Manteca” that became Barretto’s own on his debut recording with Red Garland. While he loved to play and make people dance it was the world of Jazz that would expand his perspective lifting his “muse” to higher ground, and us along with him. Ray Barretto: Un Boricua that made us proud to hear him play on American radio, made us proud to see him sharing stages and music with Chick Corea, James Moody, Kenny Burrell and Ramsey Lewis, and made us proud to dance to his music from the most prestigious music venues to the meanest streets.

His sounds are part of the soundtrack of our lives. While Hippies rocked at Woodstock, we (salseros) took the field at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx moved by the thunderous power of Boricua Barretto’s drum playing alongside the Cuban Mongo Santamaria and the African Manu DiBango. “Que Viva La Musica” was our national “street” anthem, while “La Hypocresia and Falsedad” helped us look at ourselves and stem the crabs-in-a-basket mentality that affects all poor communities. I grew up to Ray Barretto as many Latino baby boomers did. His growth in music paralleled our growth as a community, coming of age in Nueva York where we danced between cultures while keeping the clave of our African ancestral roots alive.

Written by Aurora Flores