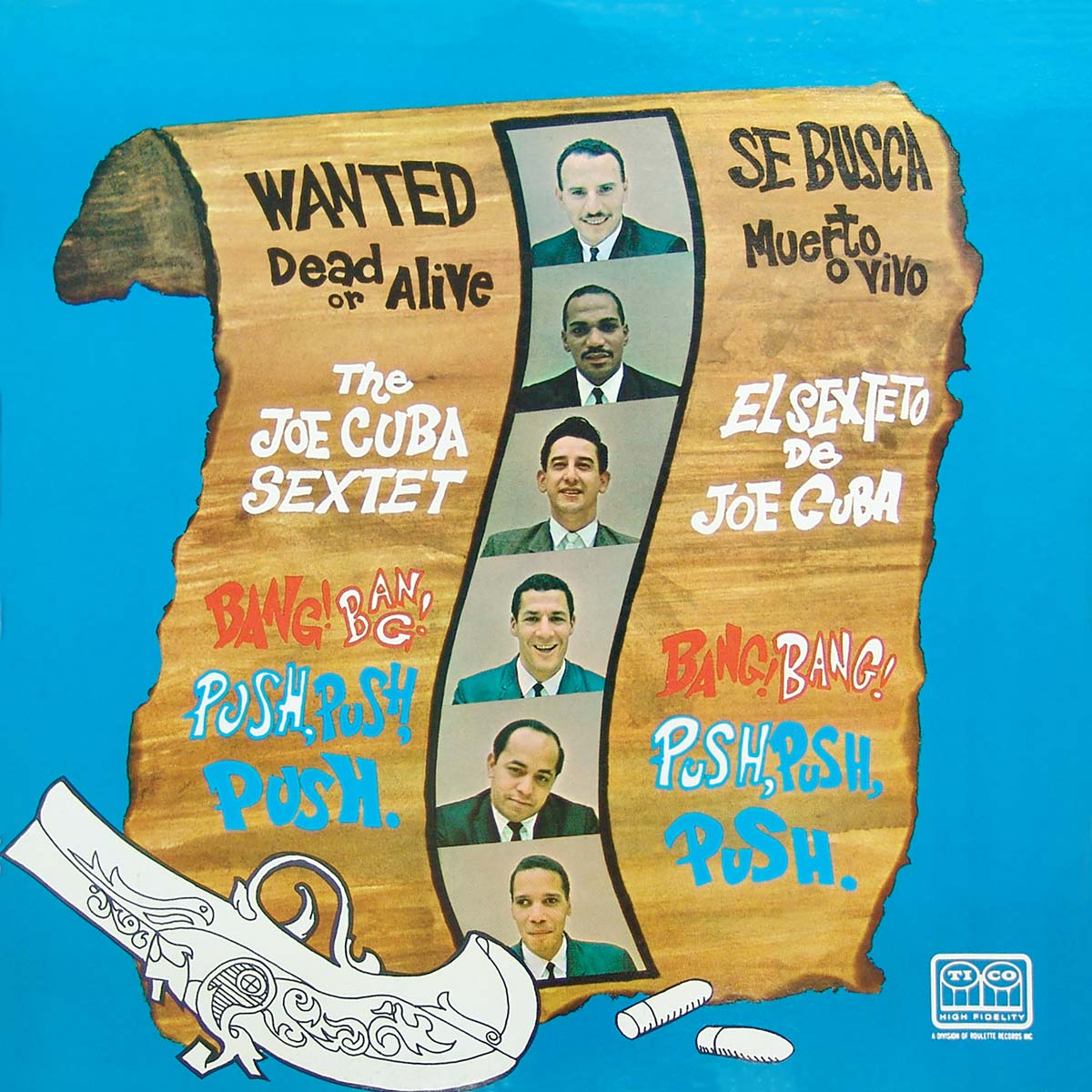

“Let’s just try it out, Sonny, if it doesn’t work, I’ll buy you a double”. The place: Palm Gardens Ballroom, mid-town Manhattan. The year: 1966. Singer Jimmy Sabater was trying to persuade his bandleader, José “Sonny” Calderón, or Joe Cuba, to implement a new idea that Sabater had in mind for some time. Reluctantly, Cuba agreed. Sabater gave pianist Nick Jiménez the tumbao (rhythm figure) and in an instant, the mainly African-American Harlem audience was singing along: “Beep beep… hah… beep beep…’” And that, more or less, is how one of 1960’s Nuyorican music’s biggest hits, Bang! Bang! Push, Push, Push was born.

Although Richie Ray’s Jala Jala Boogaloo was probably the first release to mention “boogaloo,” and, according to Sabater, was the inspiration for Bang! Bang!, it’s still fair to say that Joe Cuba and his band developed the boogaloo (bugalú ) genre to a pitch that made it acceptable to even the most hardened old-school Cuban musicians and listeners. The success of this Joe Cuba album explains in some way how Latin funk and boogaloo came about. As neighbors, African-American and Puerto Rican New Yorkers had been enjoying each other’s parties and music for years. Many seminal vocalists—such as Sabater himself, Bobby Marin and others—spent the early 1950’s catching the doo-wop echoes on the Harlem stoops with the many street-corner vocal groups of the time. Meanwhile, doo-woppers such as the Harptones were giving a reciprocal tip of the hat to Cuban and Puerto Rican peers with songs such as Mambo Boogie and Hey Señorita. Sabater himself was once quoted as describing boogaloo as “just cha cha cha with a backbeat.”

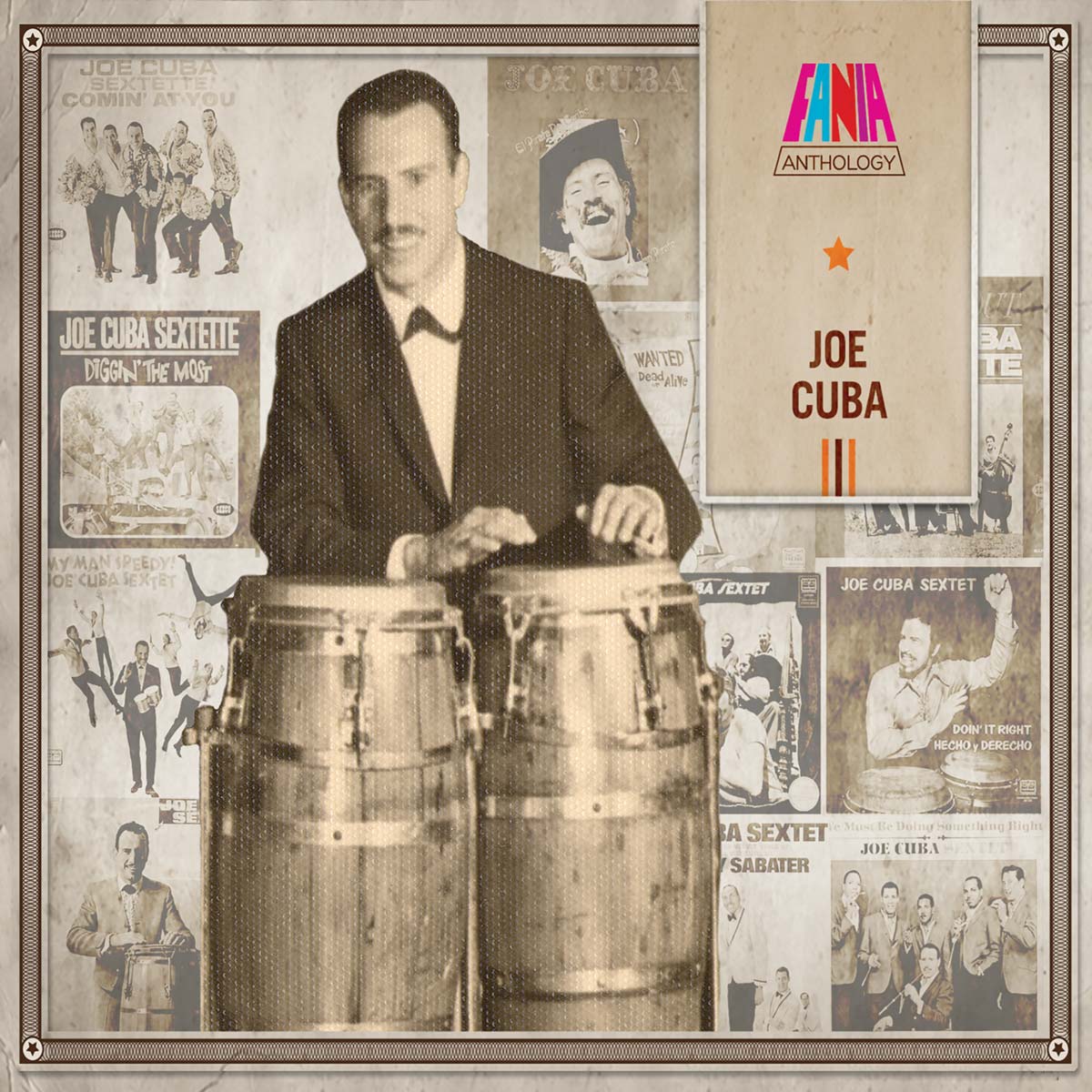

Before signing with Tico Records in 1965, New York-born vibraharpist Cuba already had a solid track record as a popular performer with cross-racial appeal, just as happy to sing vocals in Spanish as in English. He had ridden the earlier pachanga and Afro-Cuban crazes with fine releases on the Mardi Gras, Embajador and Seeco labels, when his band had featured the superb Spanish-language vocals of Cheo Feliciano. The 1962 Seeco album, Steppin’ Out, featured the massive hit ballad To Be With You, as well as the prototype salsa-descarga A Las Seis.

So it came as little surprise to those Latin musicians and fans “in the know” that Cuba’s magic touch should also extend to boogaloo. The watershed for boogaloo was the collapse of diplomatic relations between Havana and Washington, D.C., in 1961. New York’s pachanga and mambo crazes had relied on a steady flow of musical talent back and forth between the United States and Cuba, but suddenly, there was a void of talent, new “sounds” and new crazes. Enter the always present influence of African-America jazz and R&B, as well as the stripped-down, versatile six-piece line-up that was Cuba’s real innovation. Without a massive horn section to arrange for, new trends could be harnessed to the Latin chariot quickly and easily, and a multi-cultural, music-hungry public swiftly followed. So Cuba’s albums often had bi-lingual titles such Vagabundeando/Hangin’ Out or Cocinando La Salsa/Cookin’ The Salsa, etc. and were among the first artists to do so.

This particular album contains Cuba’s biggest-selling record of all time, Bang! Bang! Push, Push, Push. The tune also was released as a seven-inch single and crossed over into the international pop charts. But there are other joys here that are too easily overlooked because of that title’s overarching success: check out singer Sabater’s salsa swing on Malanga Brava and Así Soy; or the descarga Cocinando, where the musicians encourage each other “off-mike.” Sock It To Me and Oh Yeah carry the required contemporaneous Harlem swagger, while the title track is neatly restated near the end of the record in Push, Push, Push, just in case we’d forgotten how good Bang!Bang! sounded at the beginning!

In the shadow of Cuba’s and Sabater’s unique talent, it would be too easy to overlook the valuable contributions of the other members of the sextet. The rhythm section was one of the tightest in town at that time (Cuba himself being part of it). And special praise goes to pianist Nick Jiménez who played with great swing throughout this session, as well as being responsible for arranging and co-composing many of their most popular selections. Listen to the way in which the vibes slot into the percussion arrangements. Of course, the vibraharp is technically a percussion instrument. But years of listening to Cal Tjader’s more measured, improvised approach to vibes had obscured its original strengths that Lionel Hampton had first highlighted—and which Joe Cuba took into the heart of Afro-Latin party music.

Written by John Armstrong