The 70s salsa explosion is filled with so many larger-than-life characters – Héctor Lavoe, La Lupe, ‘Maelo’ Rivera – that there is a tendency to forget those superlative singers who stayed away from excess and focused instead on creating a consistent body of work. El niño bonito de la salsa, Ismael Miranda is one such singer. Miranda is arguably the only vocalist from the Fania All Stars who continues releasing excellent salsa albums to this day.

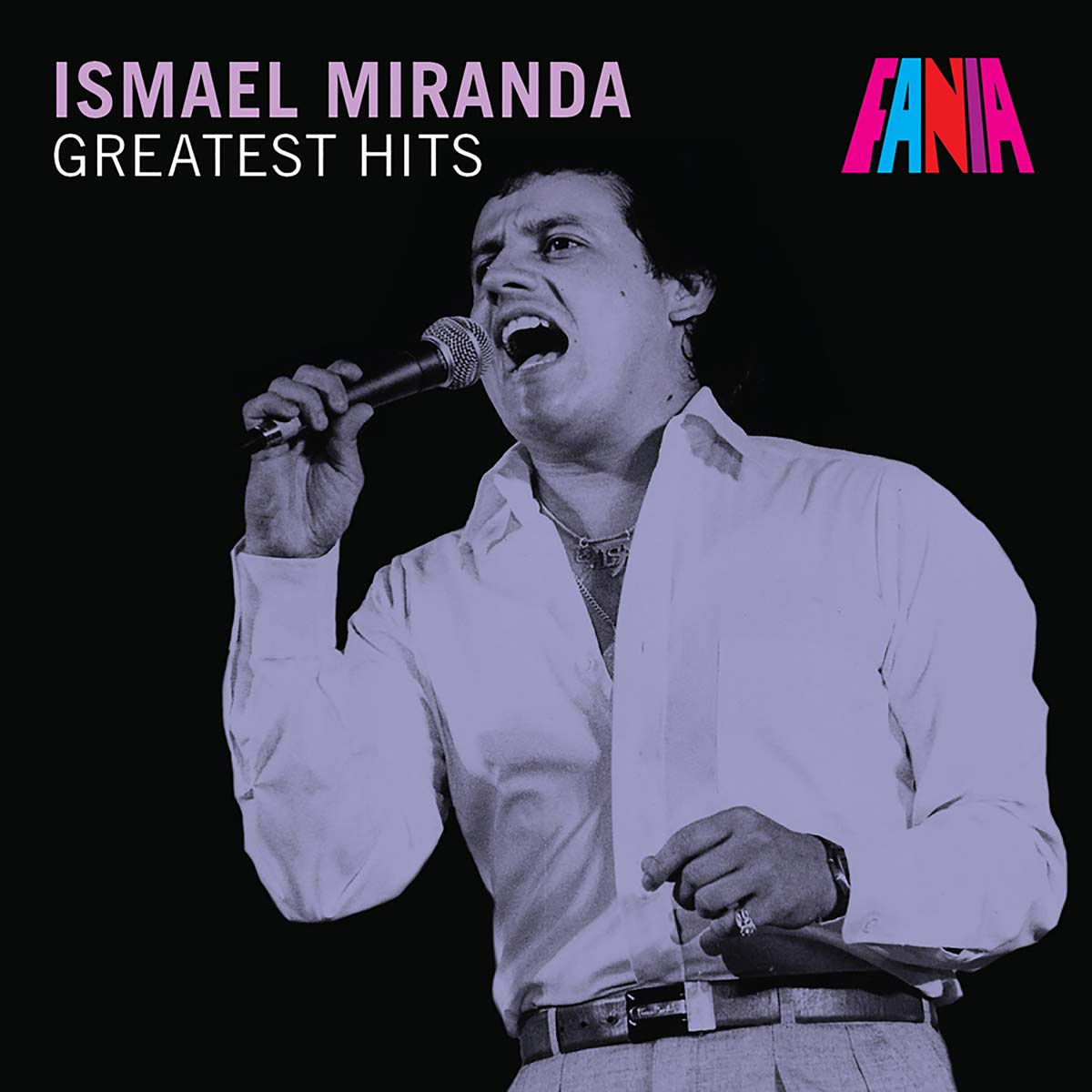

This greatest hits anthology is by no means definitive. In over 40 years of activity, Miranda has recorded dozens and dozens of hits. Simply, this CD seeks to dazzle the listener by showcasing the stylistic breadth of the man’s repertoire: el niño bonito alternated effortlessly between seminal salsa scorchers and a lush combination of bolero and ’70s pop balladry.

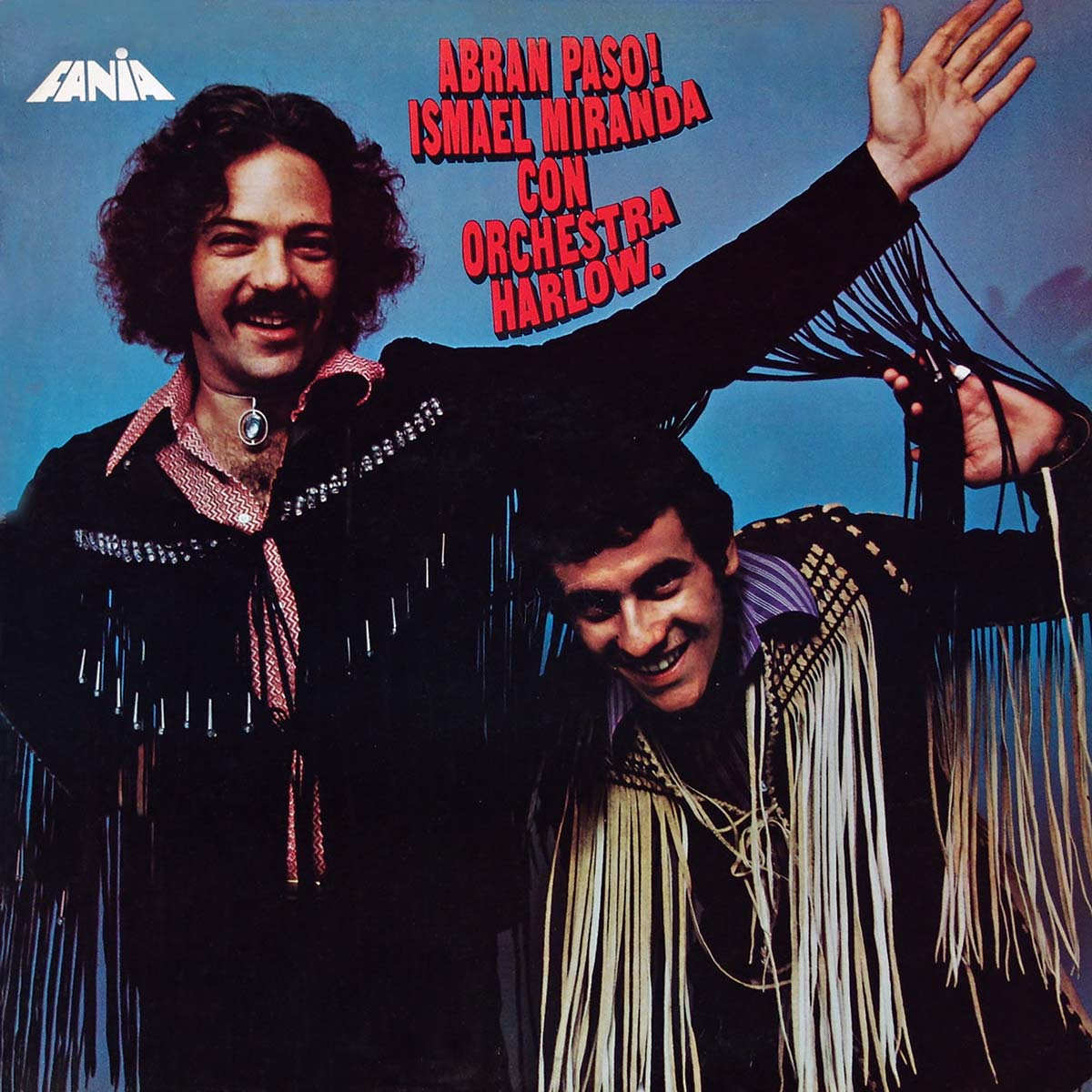

Born in 1950, Miranda moved with his family to the U.S. when he was four. At age 16, he was already performing with the orchestra of Joey Pastrana. Pioneering keyboardist Larry Harlow saw him singing with his brother Andy – and, in the summer of 1967, enlisted him as the lead vocalist of his Orchestra Harlow. Under Harlow’s artistic leadership, Miranda learned about the roots of Cuban music. “What I loved about Orchestra Harlow was that it had a real típico, Cuban sound,” says the singer from his home in Puerto Rico. “At the time, most orchestras favored a different style. Harlow was similar to Johnny Pacheco and Eddie Palmieri in following a traditional direction.” Two of the tracks here are from the classic 1971 album Abran Paso: “Se Casa La Rumba” and the title track. Harlow’s roughly hewn, swinging Cuban sound is in full display here. Soon enough, Miranda felt the desire to spread his wings and take full command of his career.

Like many salsa stars from the ’70s, he became a solo artist. This transition was engineered through the album Oportunidad. Not surprisingly, the split was initially acrimonious. “Larry opened a lot of doors for me,” offers Miranda. “In a way, much of what happened in my career, including my participation in the Fania All Stars, I owe it to him. I was very grateful about those opportunities, and I still am.” In 1973, Miranda introduced his new band, Orquesta Revelación, which included a young Oscar Hernández on piano and Nicky Marrero on percussion. Their album together, Así Se Compone Un Son, is thought by many to be the singer’s finest solo effort to date. The sound is somewhat smoother than Orchestra Harlow’s – but Miranda maintained his rugged soneos on songs like “Las Cuarentas,” a tropicalized version of the classic tango previously recorded by Cuban singer Rolando Laserie. Looking for a complete lifestyle change, Miranda moved to Puerto Rico – calling the island home since then. “Living in Puerto Rico improved my diction in Spanish, which had given me some trouble at the beginning of my career in New York,” he explains. “Most importantly, I now had a staff of people who worked for me and helped me organize my concert engagements. I wasn’t alone anymore, which gave me a feeling of security. Everything was easier. I had more faith in myself, too.”

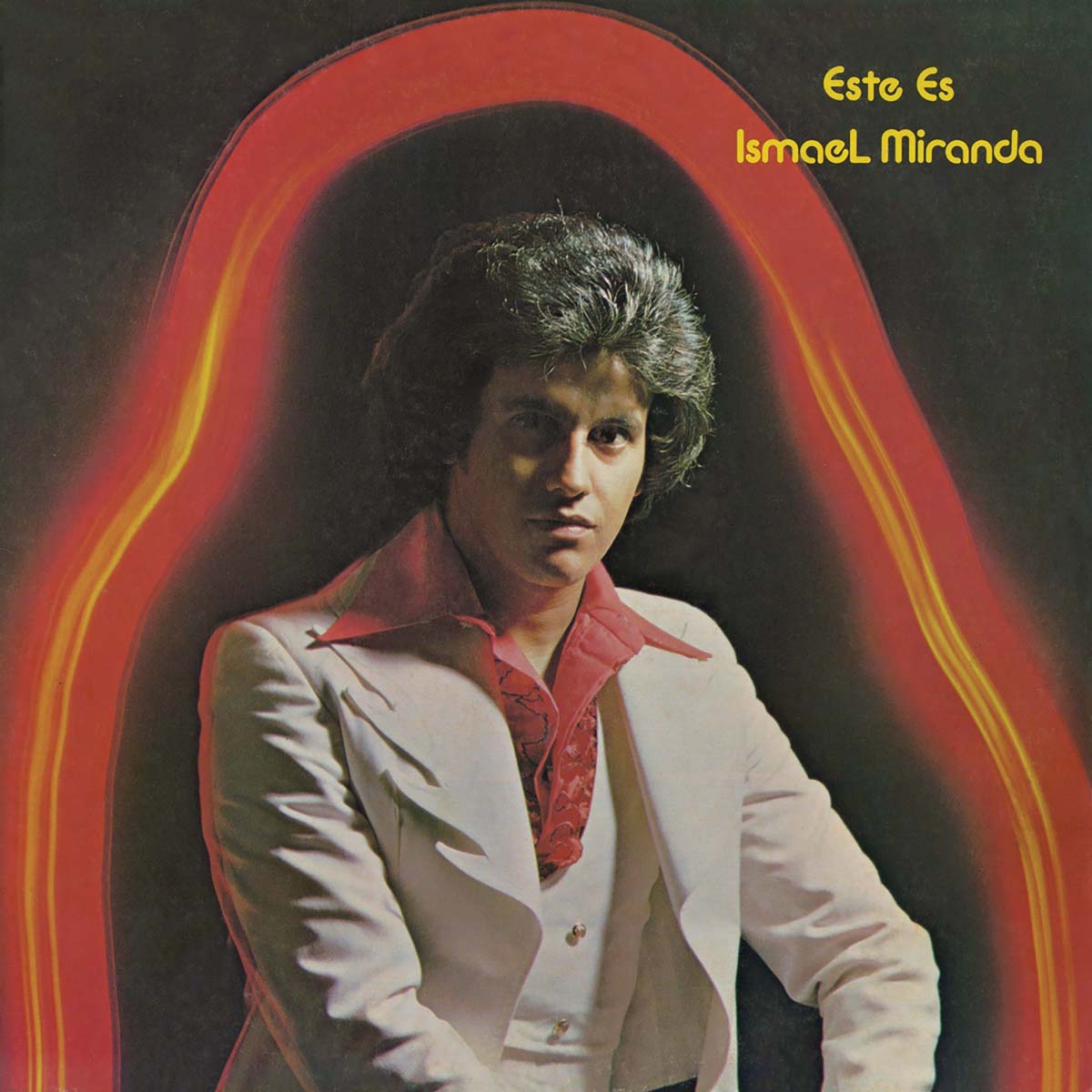

In 1975, the blockbuster LP Este Es Ismael Miranda found him in full control of his singing and songwriting abilities. Miranda was now marketed by Fania as a dashing crooner of syrupy ballads – dressed in a white costume on the cover. And by combining the bolero aesthetic with a more contemporary sound (the use of trap drums, electric guitars, and lavish pop arrangements), he was now competing with mainstream Latin singers like José José and Armando Manzanero. Still, the album was wonderfully eclectic. “María Luisa” delivered Afro-Cuban sparks at the speed of light. Rubén Blades’ “Cipriano Armenteros” includes the Panamanian singer’s inspired coro, wailing trumpets and an epic narrative. “En Mi Viejo San Juan” revamped the venerable bolero for a younger generation.

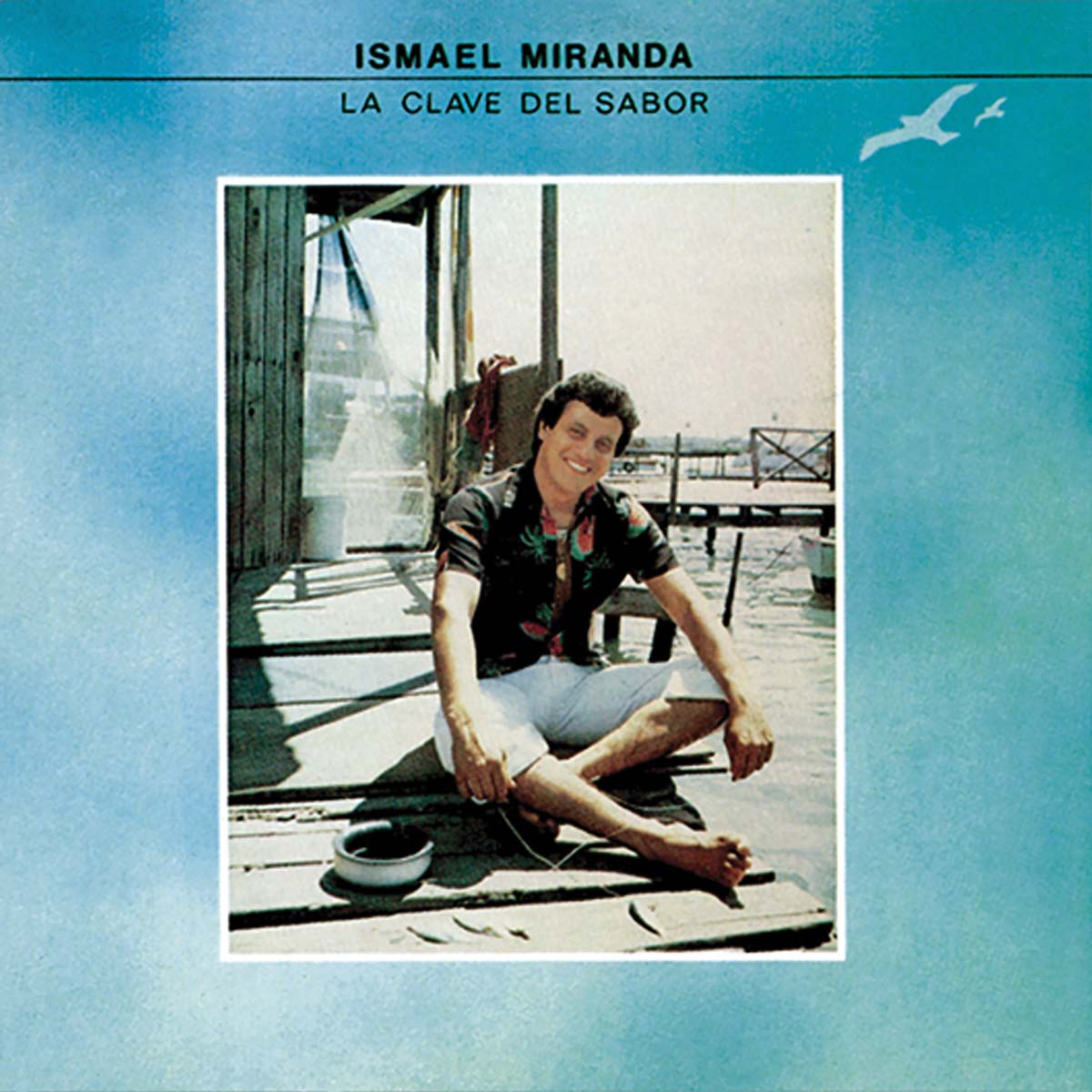

Miranda continued developing this unique approach to tropical balladry on subsequent albums. In 1977, No Voy Al Festival included the velvety “Tú Me Abandonaste” (underscoring Miranda’s chops as an old school sonero), and “La Puerta Está Abierta,” with its soulful instrumental break of drums and electric guitar. One of the most fascinating (and misunderstood) albums in Miranda’s career was Doble Energía. Released in 1980, it was meant to generate a massive hit by teaming up the singer with ace producer Willie Colón. But the chemistry that emerged so effortlessly when Willie worked with Celia Cruz, Héctor Lavoe and Rubén Blades was strangely absent from this album. That said, Miranda’s voice sounds particularly soulful enveloped in Colón’s trademark layers of trombones – check out the sonics on “No Me Digan Que Es Muy Tarde” and “Cartas Marcadas.” The most recent songs in this collection are the gritty prison tale “Galera Tres” and the lilting ballad “Yo No Me Vuelvo A Enamorar” – both from the 1981 album La Clave Del Sabor. Needless to say, Miranda would continue creating salsa hits for decades to come – surviving the forgettable salsa romántica fad and emerging into the new millennium with his reputation as an authentic sonero intact.

Liner Notes by Ernesto Lechner