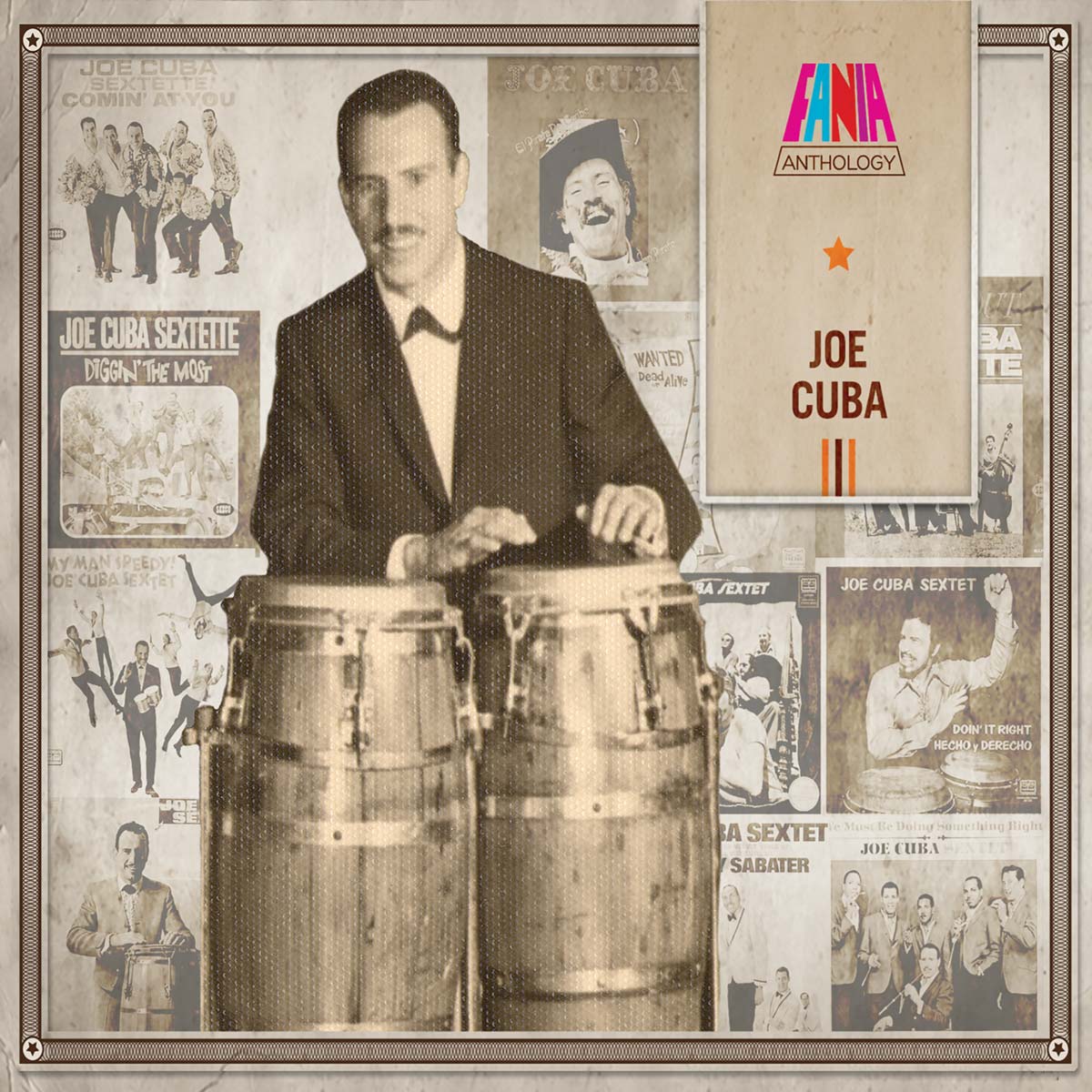

The Joe Cuba Sextet recorded countless hits across the decades, each embodying the soul of Spanish Harlem and capturing the sounds of the first generation of New York Puerto Ricans. With hustler instincts, Joe and his band—originally consisting of Jimmy Sabater on timbales and vocals, Tommy Berrios on vibes, Nick Jiménez on piano, Roy Rosa on bass (replaced early on by Jules Cordero), and Willie Torres on vocals—reinvented the Latin sound several times over.

There’s little doubt that salsa owes its swagger and swing to Joe Cuba. Joe’s pride for his neighborhood spilled over into his playing, made his sound contagious, and birthed a movement reflective of Spanish Harlem’s vibrant soul. Joe’s unique childhood gave him a cross-cultural perspective that would later imbue his music. Born to Puerto Rican parents struggling to survive the Great Depression, a young Gilberto Navarro (later, Calderón) and his brother grew up in foster care with a White, English-speaking family on Staten Island. After five years, Joe and his brother were reunited with their mother, Gloria, in Spanish Harlem, where he first heard Spanish being spoken. Rediscovering his language and roots at such a young age gave Joe a special appreciation of his heritage. New to the hood, Joe earned his stripes sliding hard into makeshift bases while playing stickball on the concrete of 116th Street—they would run away from police in the back-ally canyons of Spanish Harlem when games would get broken up; they would chill on stoops in the evening and kick game to the girls from around the way. He started his music career at the end of his stickball career: “I broke my leg sliding into second base, and I was in a cast for a while. So a friend of mine lent me his conga, and I would practice to Machito records.” Like many aspiring Latino musicians in the U.S. at that time, Joe found inspiration in the Cuban-born Latin jazz legend Machito, but growing up next door to the scene’s future talent also helped. “There were a lot of musicians on my block,” he said.

“Santo Miranda, Negrito Pantoja, and Sabu Martinez, these guys would hang out on the block and motivate me.” When Sabu Martinez took a job in Hollywood, Joe replaced him and became the conguero for La Alfarona X, New York City’s first Puerto Rican trumpet conjunto. It was a short stint (Sabu eventually came back to claim his spot in the band), but Joe got a taste of what it was like to be a musician: “If you were a regular guy, the girls would just walk by, but if you were playing an instrument and singing a coro, they’d stop! And then you could rap to them.” The band gained momentum after sonero José “Cheo” Feliciano replaced Willie Torres in 1958. Cheo’s swingin’ and smooth singing in Spanish complemented Jimmy Sabater’s crooner-style English vocals, giving the band appeal to both English and Spanish audiences. “Cheo had a thick accent; that’s when they put me in to sing in English,” Jimmy remembers. “Cheo would sing one bolero in Spanish, and I would sing one in English.”

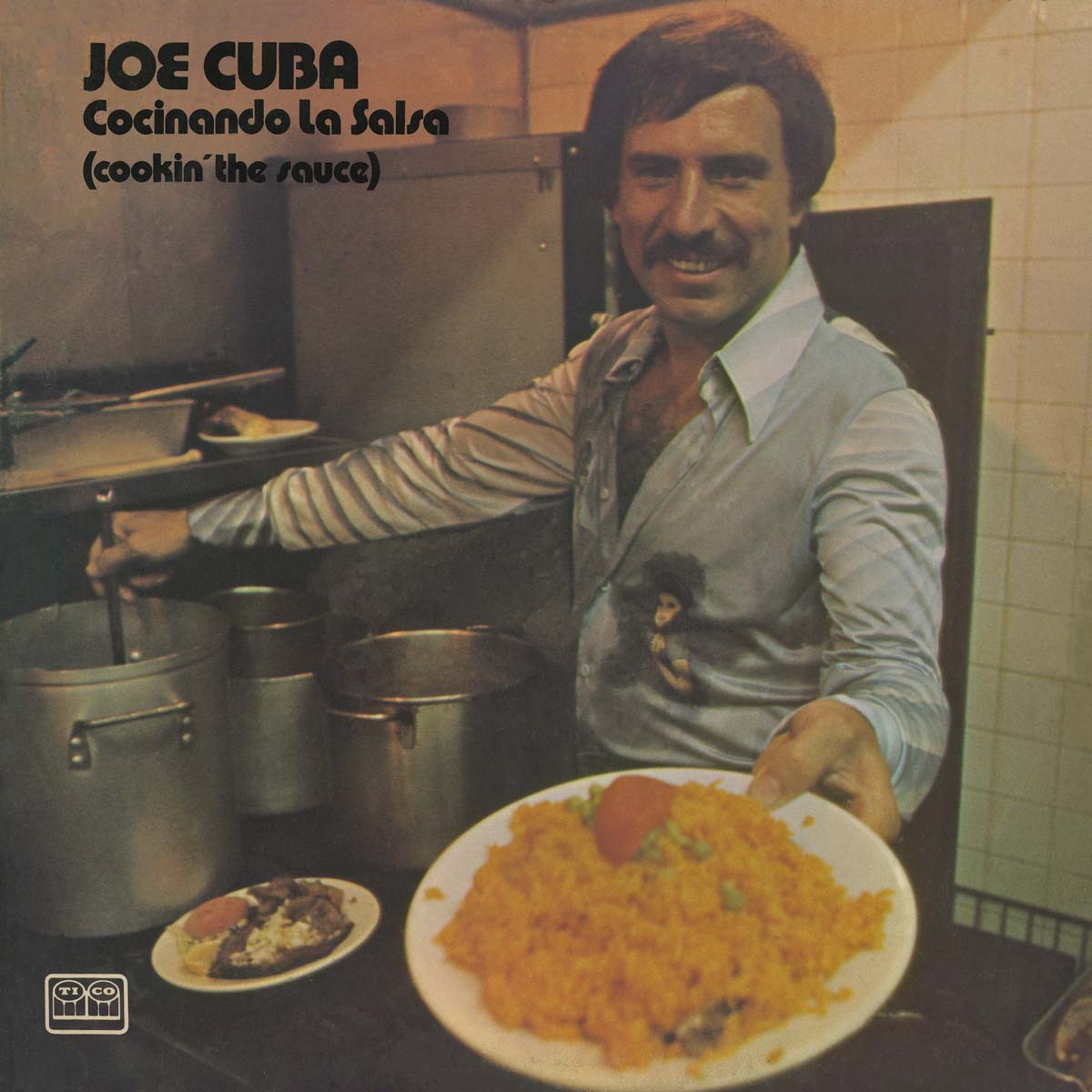

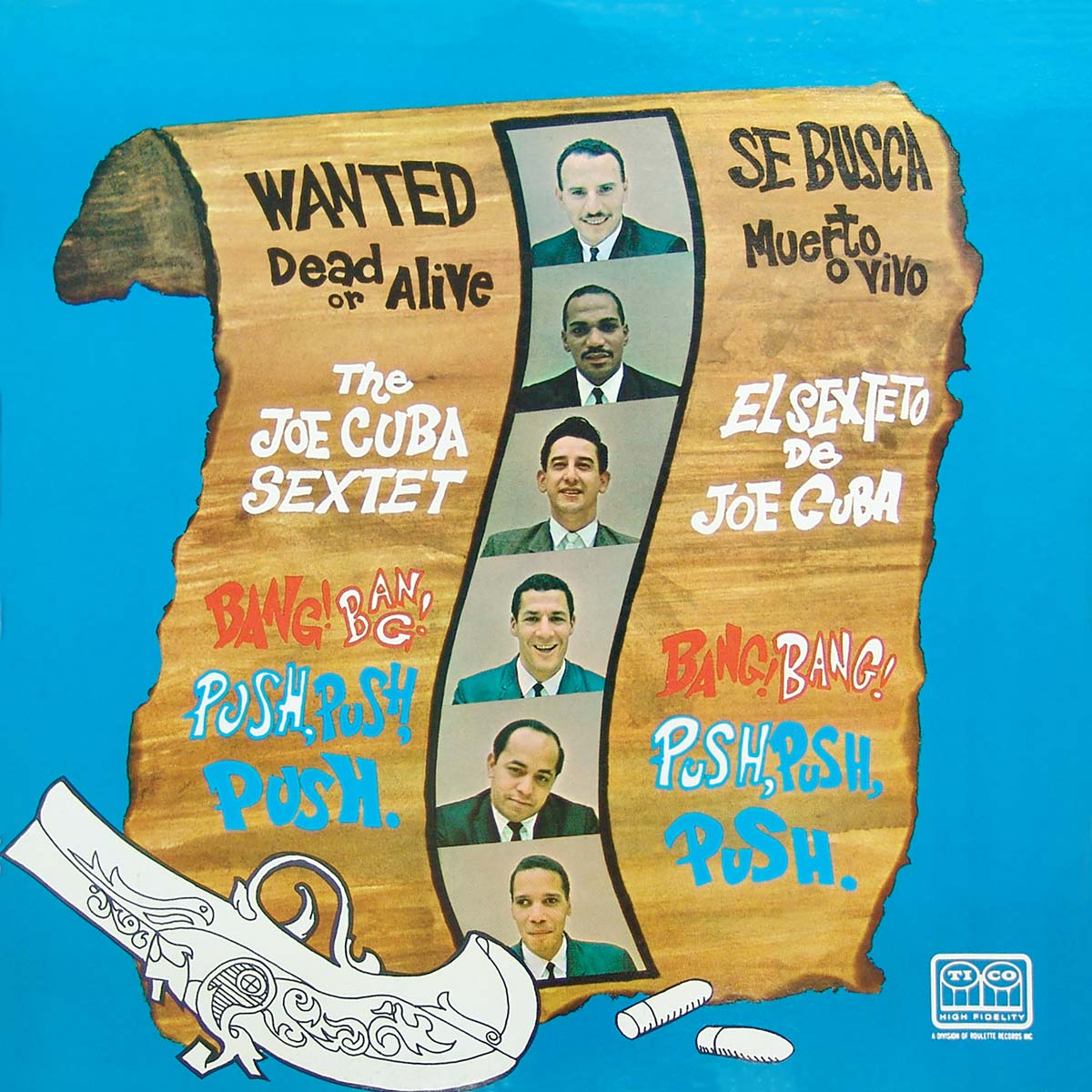

It was this combination that made the sextet’s Seeco Records debut, Steppin’ Out, a crossover hit. Laced with hits like “A las Seis” and “To Be With You,” Steppin’ Out displayed the band’s bilingual versatility and dual shades of Nuyorican soul. The band perfected their bilingual harmony with “Bang! Bang!” the monster hit that inspired Latin soul and boogaloo, striking a chord with New York’s growing bilingual Puerto Rican community. Gritty and slightly offbeat, “Bang! Bang!” was a tour of Harlem put to music. The love for home and the swagger that the Joe Cuba Sextet brought to their music inspired the same pride, love, and attitude in younger musicians. For all his pride, Joe never took all the credit for salsa himself. He recognized the work put in before him and the contributions of his peers: “In the ’50s, our music broke out, especially when Rodríguez, Puente, and Machito started opening doors downtown at the Palladium; and then I came along with my sound, and Eddie [Palmieri] came with his trombone, and Pacheco started Fania; we were building.”

More than his innovation to New York Latin music, Joe will always be remembered for the love he brought to his music. For him, fame was secondary; representing his barrio and the joy of playing were enough.

– Liner notes by Kristofer Ríos