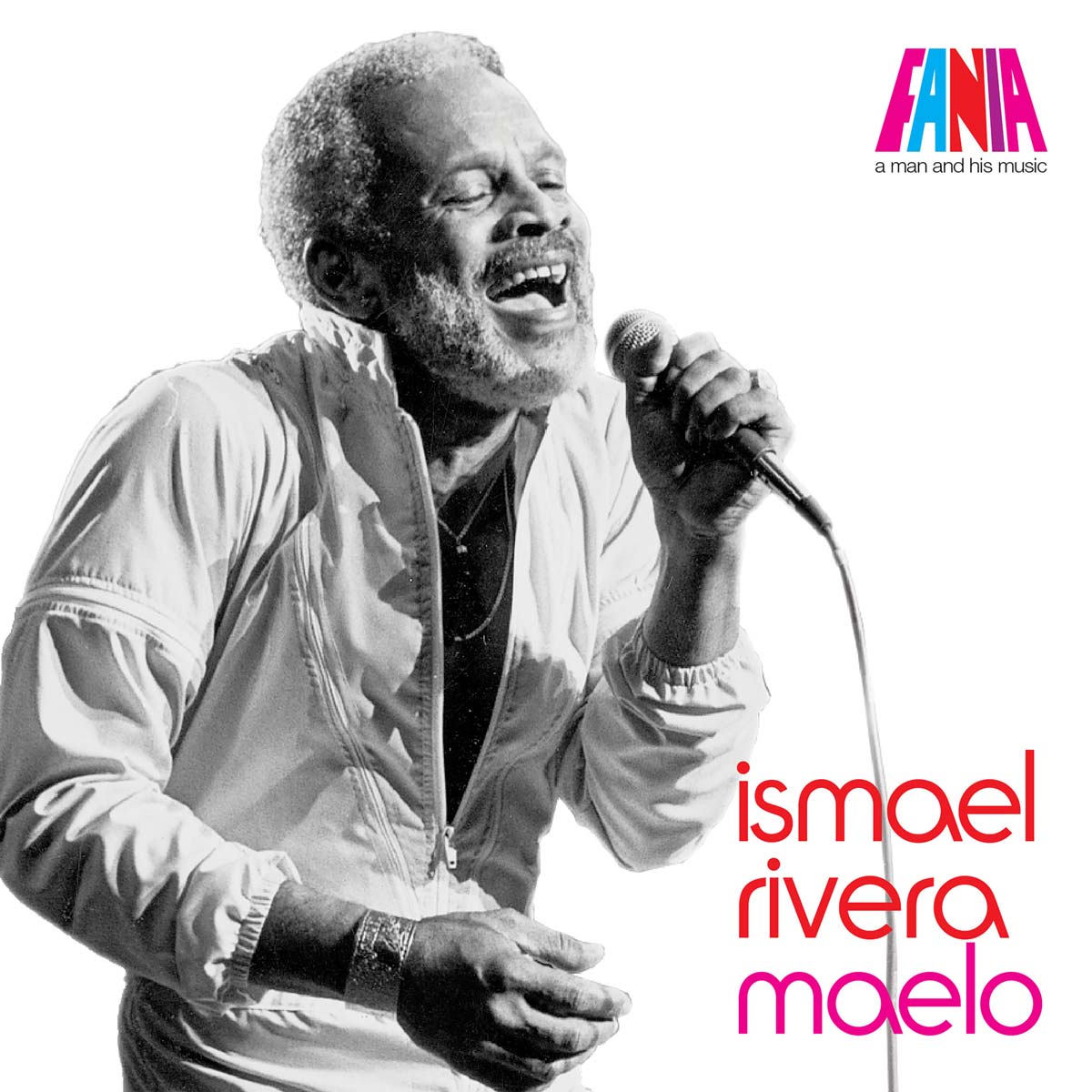

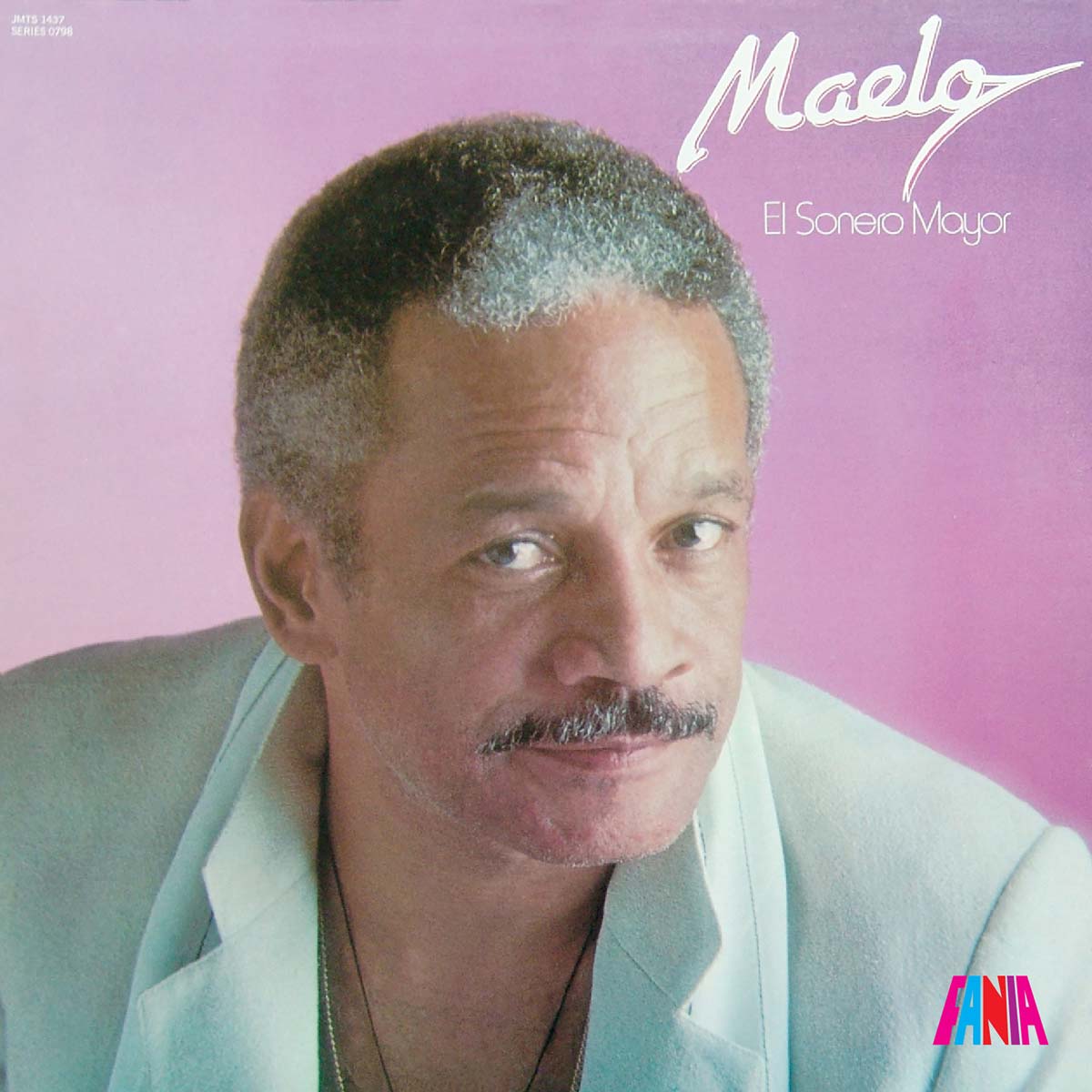

Ismael Rivera, El Sonero Mayor, a Puerto Rican salsa pioneer, vocal innovator and master of poly-rhythm, beloved by fans and admired by peers. In Panama, there’s a virtual cult surrounding Rivera, a devotee of that country’s Cristo Negro de Portobelo. “Maelo is the first who decides to ‘break clave,’ ” says Rubén Blades, Panama’s premiere salsero. “He invaded the spaces where the chorus started, which made his phrasing so powerful and thrilling. He didn’t wait his turn to ‘sonear.’ ”

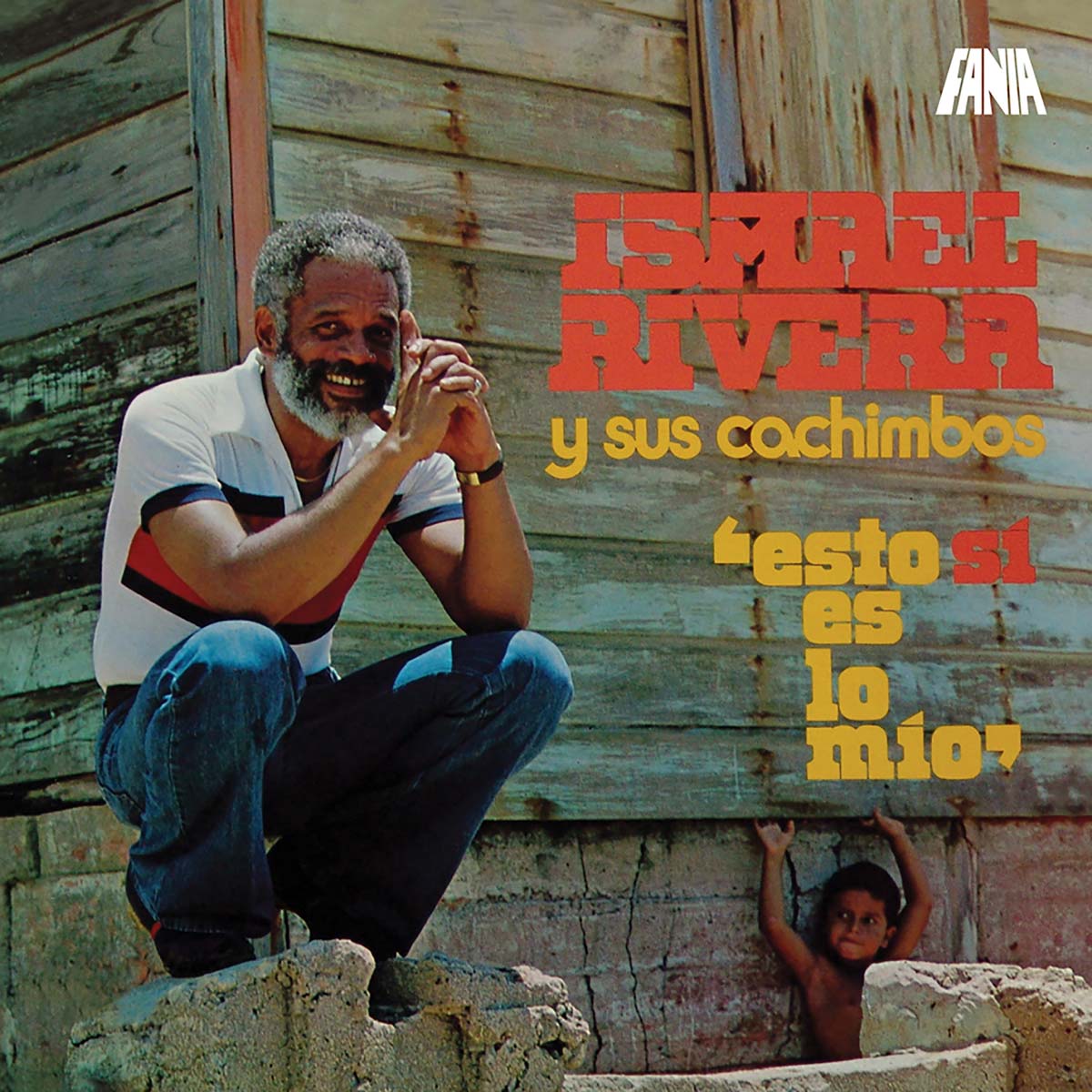

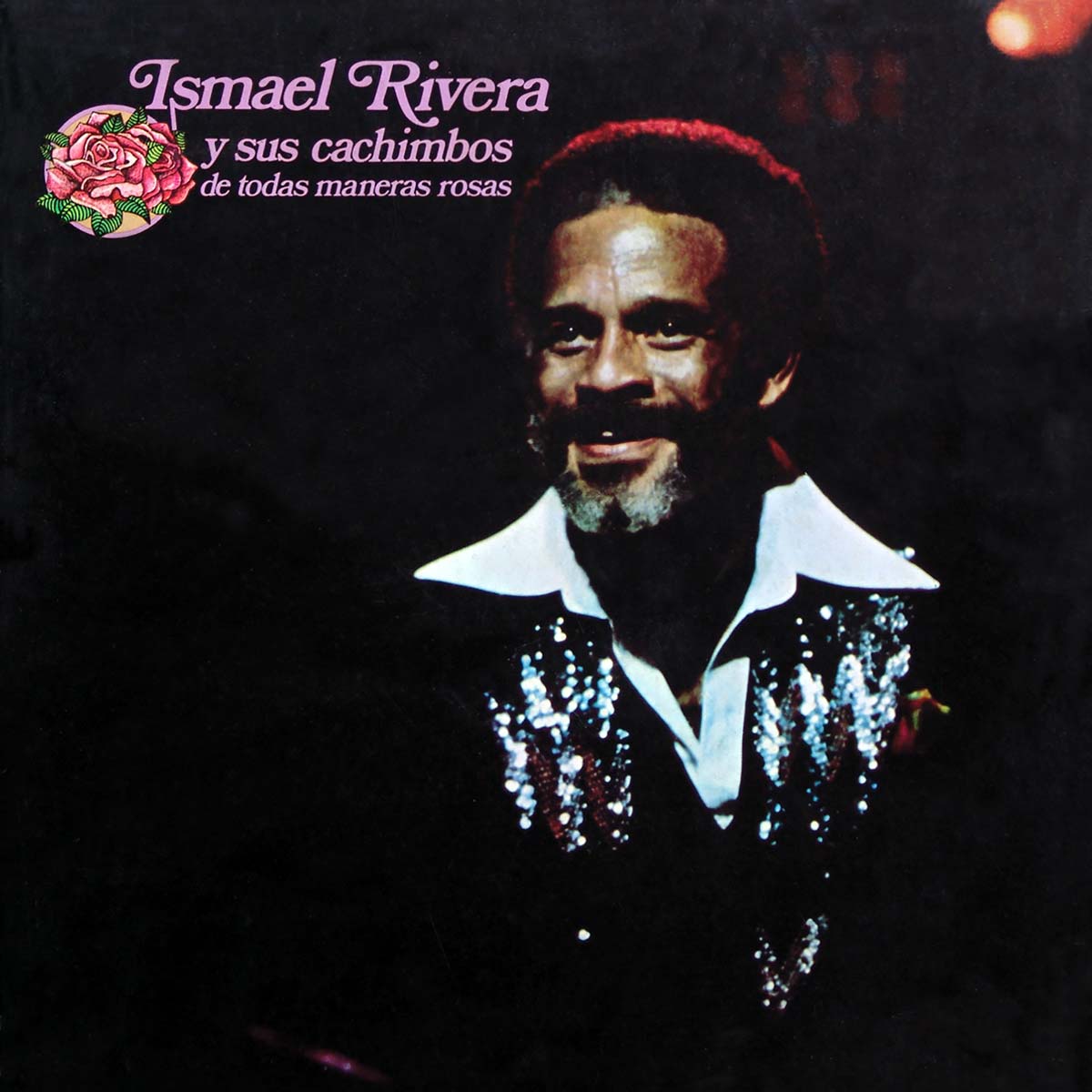

I first heard of Ismael Rivera in the summer of 1974 when El Sonero Mayor was already enjoying a late-career comeback. It was all new to me, a California college student seduced by salsa as a window on Caribbean culture. When a friend brought me a new album from New York, Traigo de Todo, I studied the artful cover for clues to this mysterious artist, El Brujo de Borinquen. The front shows only a clenched fist with a dainty daisy popping out between the fingers.

On the back, we see the man attached to the hand, a middle-aged mulatto with a salt-and pepper beard, furrowed forehead and eyes of kindness, but also sorrow and struggle, like the weathered face of an old blues man. That visage seemed to capture the essence of this music, born of the joys and suffering of downtrodden people. His rhythmic daring and dexterity is evident in “Dime La Verdad,” one of two tracks on this collection with Rafael Cortijo, the seminal Puerto Rican bandleader who first urged his childhood friend to become a singer, instead of a bricklayer.

This song is from the duo’s golden years in the 1950s, a time of social breakthroughs for blacks, represented on the island by the success of baseball heroes Roberto Clemente and Orlando “Peruchín” Cepeda. Cortijo and Rivera also dreamed of hitting it out of the park. As the singer once told Venezuelan radio personality César Miguel Rondón, author of El Libro de la Salsa: “It wasn’t a planned thing, you know, it was just one of those things that happened. It was all a people’s thing, a black thing. It was as if a cage was opening for us, and there was rage and Clemente started swinging his stick and that’s where we came in, you know, with our music. And it seems that same desire of ours to get out, to put an end to the ghetto, was what later made us a bit more premeditated. It’s just that we were hungry, Cesar. We were hungry.”

After serving prison time on drug charges, Rivera reunited with Cortijo in 1966 and recorded Arrecotín Arrecotán the following year. But the comeback flopped and Rivera went solo in 1968, finally finding renewed success as a respected elder of the 1970s salsa boom. Most of the songs here are from that period, including his classics “El Nazareno” and “Las Caras Lindas,” which includes Rivera’s famed vocal improvisations over Mario Rivera’s tres solo. By this time, Rivera’s voice and vigor were clearly waning. Yet, his impact and influence stayed strong. On the inside of that double-gate album cover that so captured my attention 35 years ago, Rivera is reclining in jeans and hip sneakers. He has a raised eyebrow and the faint smirk that evokes the saying, “Mas sabe el diablo por viejo…” Or as Rondón puts it: “What his voice didn’t deliver, his wisdom did.”

Liner notes written by Agustín Gurza