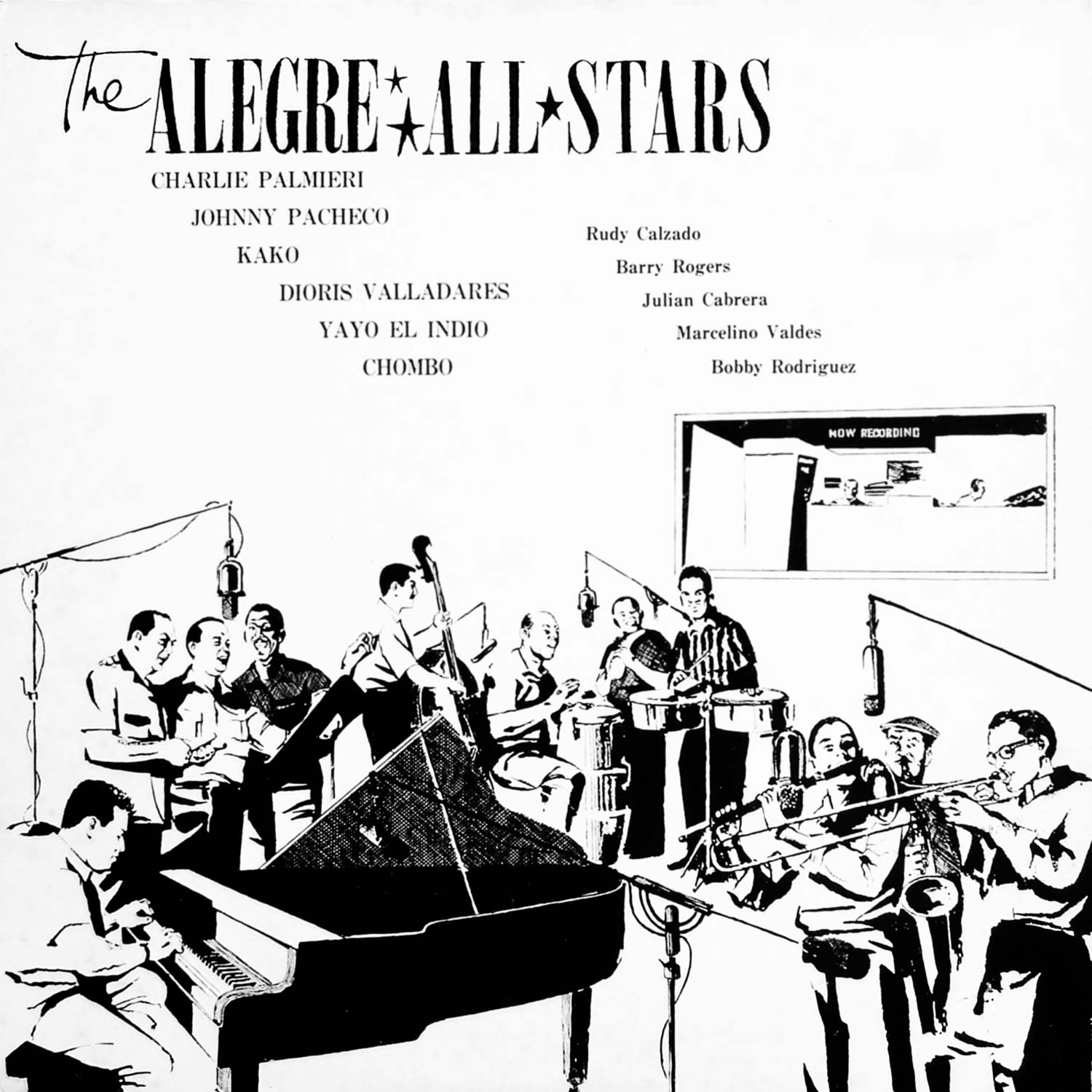

Al Santiago is Alegre Records. He had a unique style of recording. Using some of the best Latin musicians of New York helped make Alegre All Stars recordings historic. But the fact that the mics were always open, during recordings as well as when not recordingexplains the looseness and spontaneity of these recordings. They are fun to dance to, listen to and be a part of. I had the honor of assisting Al in many of these recordings and found every moment to be a learning experience for this young producer, over 60 years ago.

THE MYSTIQUE OF ALEGRE RECORDS

There is an aura of mystery and fascination that surrounds the Alegre record label and its founder. One can’t help but wonder where Latin music would, and salsa in particular, be today without the presence of Al Santiago.

Let’s imagine for a moment that Santiago hadn’t been there at that particular time and place. Would somebody else have discovered Johnny Pacheco? And what about Charlie Palmieri’s Alegre releases? Without them, would the ubiquitous pachanga become the exciting dance craze that impacted the Latin scene in the early ’60s? Would Willie Colón and Joe Bataan have recorded the sessions that ultimately motivated Pacheco to sign them to his new label, Fania, in 1966? Would Fania Records exist if Pacheco hadn’t been discovered by Alegre first? Clearly, there would be no Fania All Stars, since this particular super group was patterned after the Alegre All Stars. And Eddie Palmieri? Would somebody else have shown the vision to finance the seminal La Perfecta records? Would the success of Chivirico Dávila, Orlando Marín, Kako y su Combo, Dioris Valladares, Mon Rivera and Willie Rosario have become a reality without the marketing savvy of the Alegre label?

I was 25 years old, a Nuyorican freshly discharged from the US Air Force, when I met Al at the Casalegre record store. It was 1966, and Al was in the middle of producing two bands from the Bronx for his new label, Futura Records. He hired me as his assistant, probably because I owned a car, and he didn’t. During the day, I attended meetings with artists, record distributors, and radio DJs Symphony Sid, Dick Sugar and Polito Vega. At night, I helped with the recording sessions. The only other person who came with us to all those functions was a teen artist by the name of Willie Colón. The other musician that Futura was recording at the time was Joe Bataan.

I recall sitting at a recording console next to my mentor, Al, as he was getting ready for Willie Colón’s debut recording. The first track was an instrumental called “Jazzy.” It was done in less than 20 takes, and the band had warmed up for the next number, “Fuego En El Barrio,” which would become the first 45 rpm single in the Futura catalogue. Al was working hard, but he was eventually forced to relinquish the sessions of his young discoveries due to lack of financing. It was sad for me to witness this, but it was also exciting to watch a master at work under such difficult conditions.

Earlier that year, Santiago had been forced to sell Alegre due to financial difficulties resulting from his declining health. The buyer was Branston Music, a company operated by Santiago’s principal competitor, Morris Levy, owner of the thriving jazz/pop label Roulette Records. In 1957, Levy had already acquired the legendary Tico Records from George Goldner, due to Gåoldner’s weakness for gambling.

Having control over the Tico and Alegre catalogues gave Levy the power over the Latin music industry that he had lusted for. Ironically, tax liabilities would force him to sell both labels to Jerry Masucci’s Fania empire in 1975. 30 years later, the Miami-based Emusica Records would acquire the complete Fania archives, including historical releases on Mardi Gras, Cotique, Inca, and Vaya Records, remastering the original recordings for international release in the new millennium.

Written by Bobby Marín

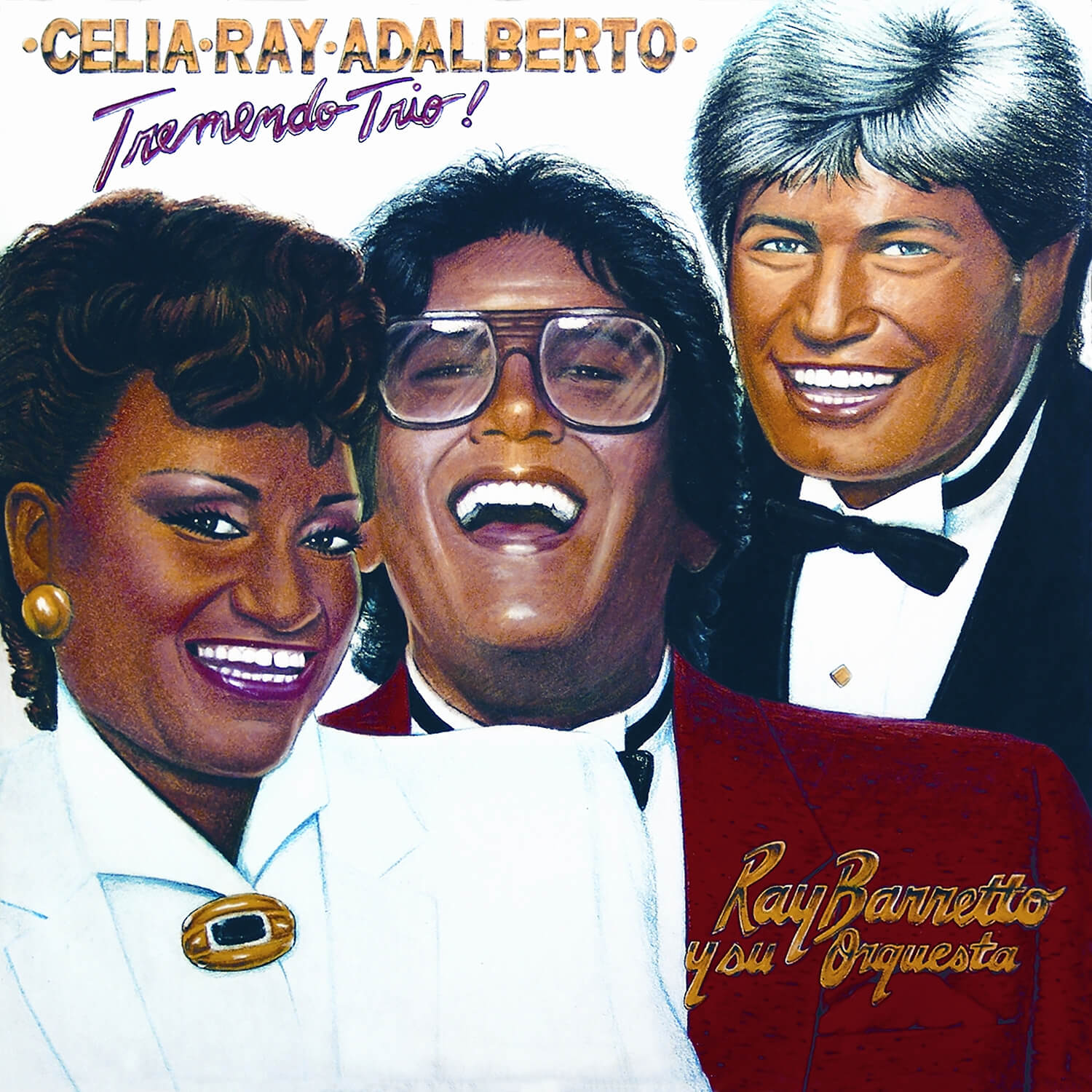

Ray Barretto, Adalberto Santiago & Celia Cruz – Tremendo Trio

Navidades Con la Sonora Matancera

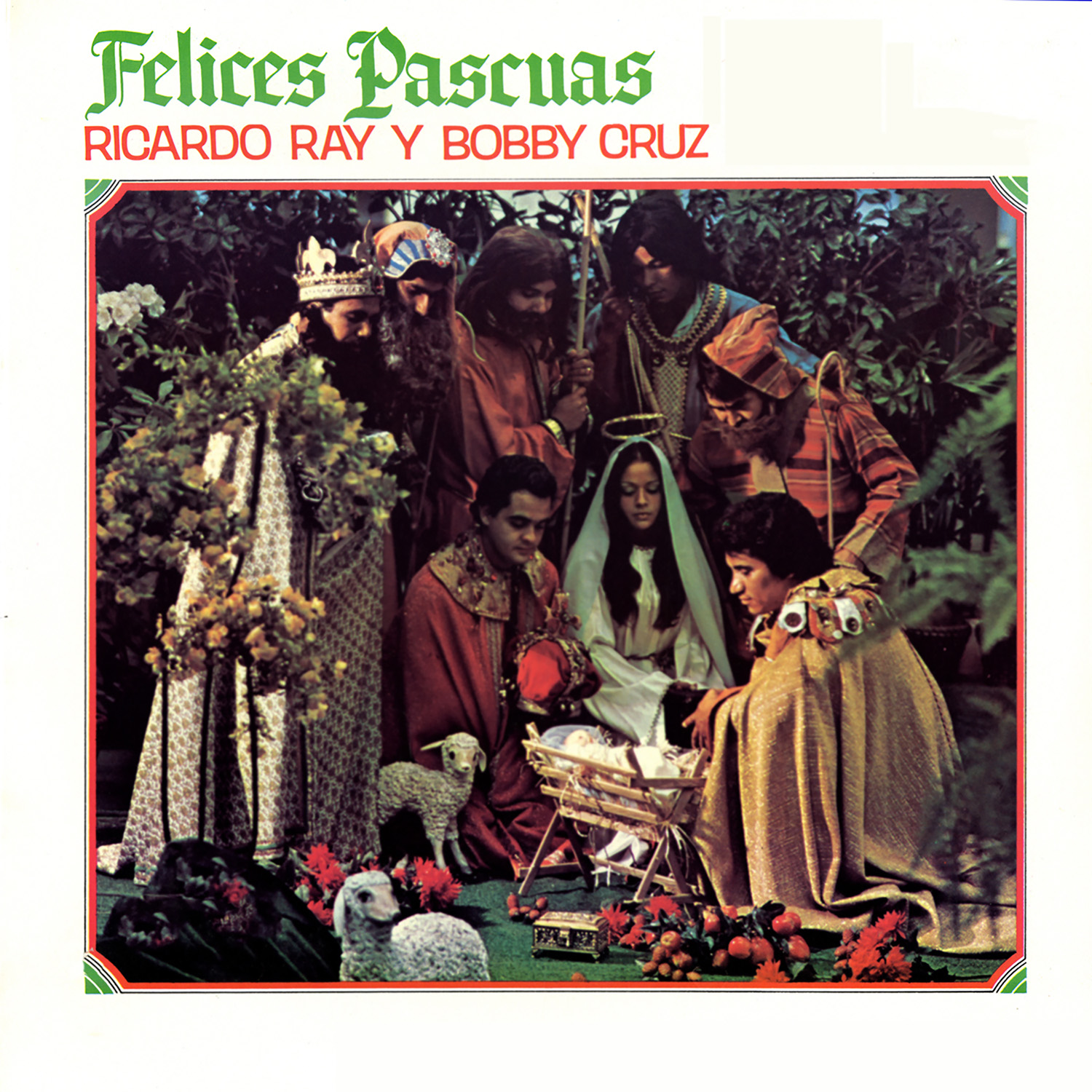

Bobby Cruz & Ricardo Ray – Felices Pascuas

Sonora Ponceña – Navidad Criolla

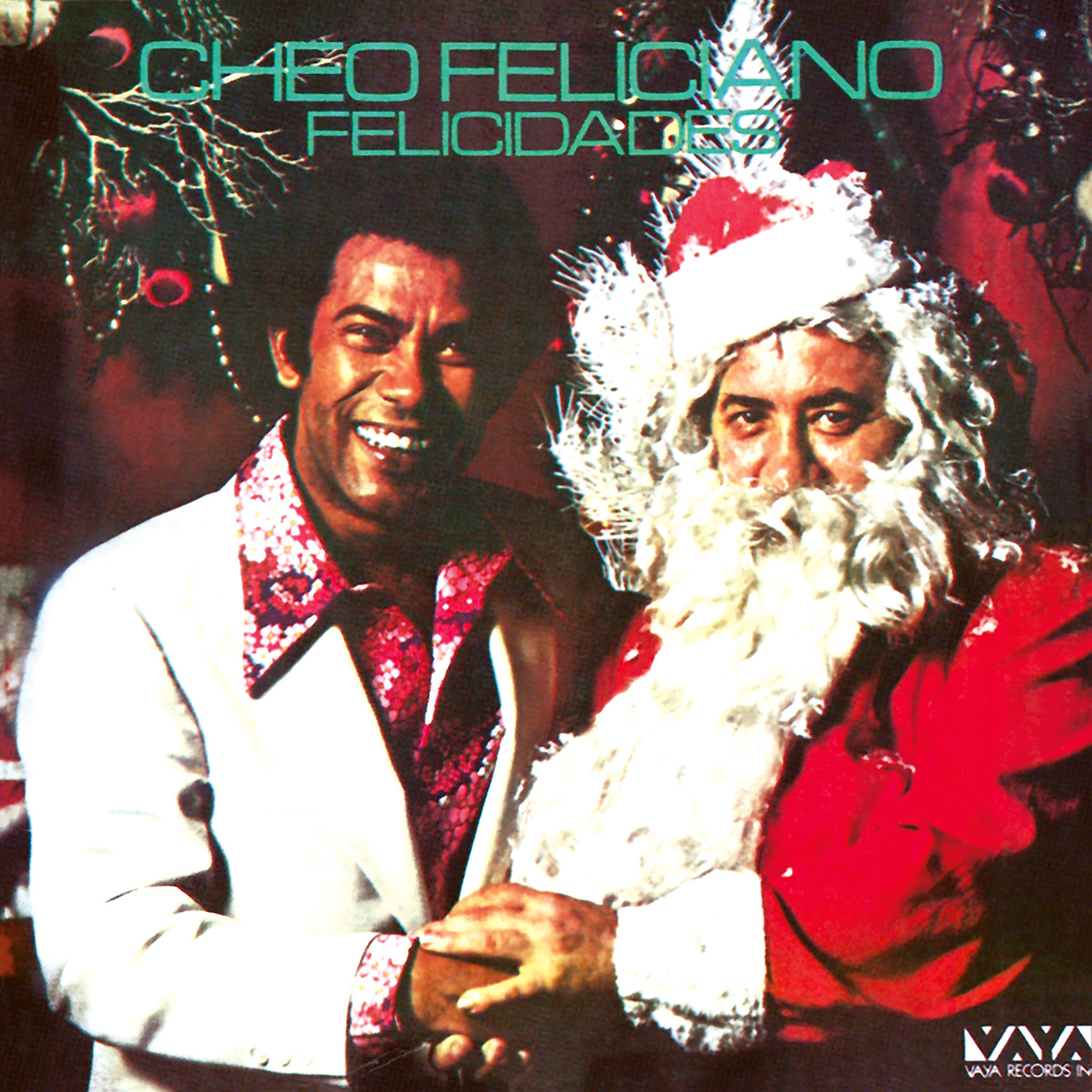

Cheo Feliciano – Felicidades

Héctor Lavoe, Willie Colón & Yomo Toro – ASALTO NAVIDEÑO VOL. II

Ismael Rivera – Feliz Navidad

PETE RODRIGUEZ – BOOGALOO NAVIDEÑO

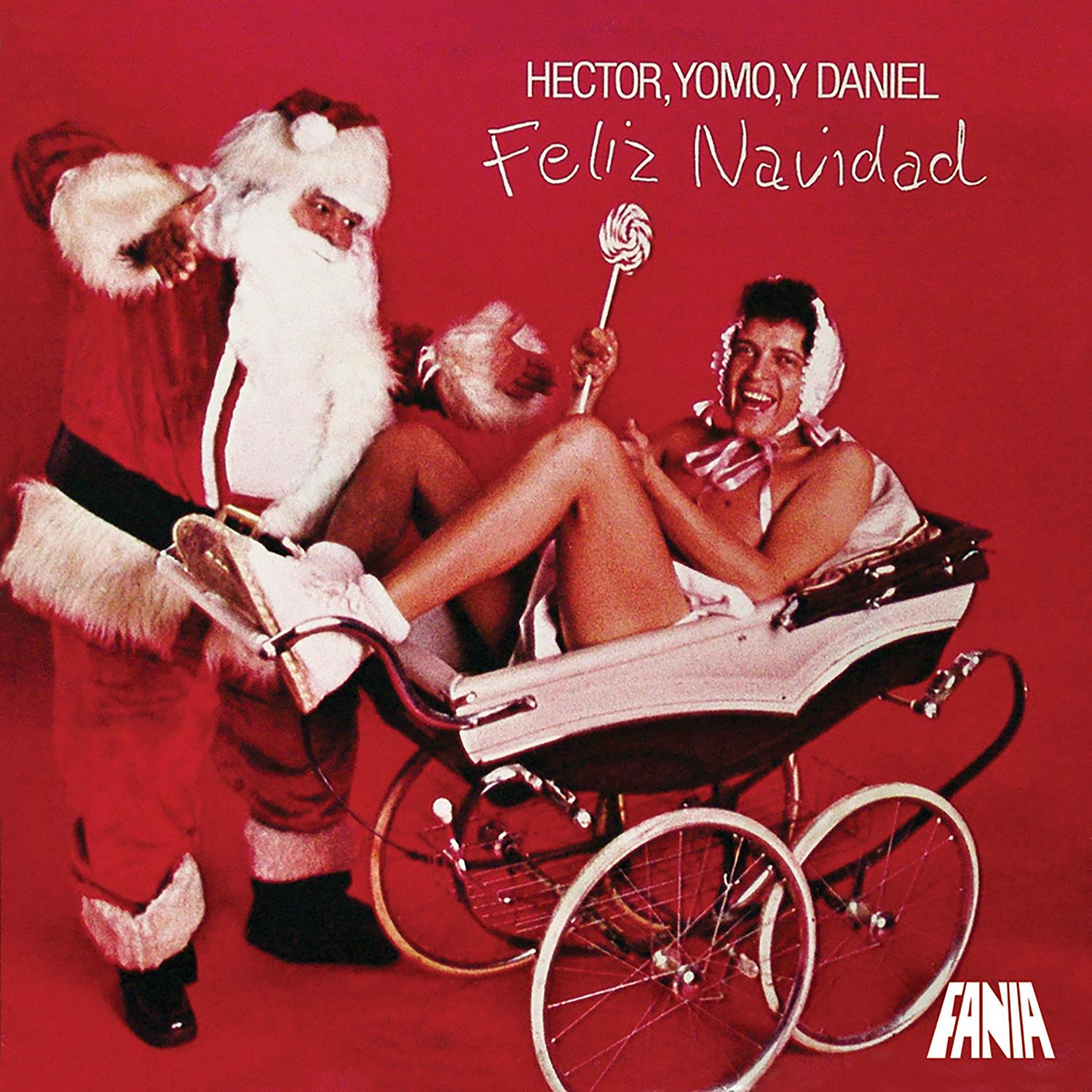

Héctor Lavoe, Daniel Santos & Yomo Toro – Feliz Navidad

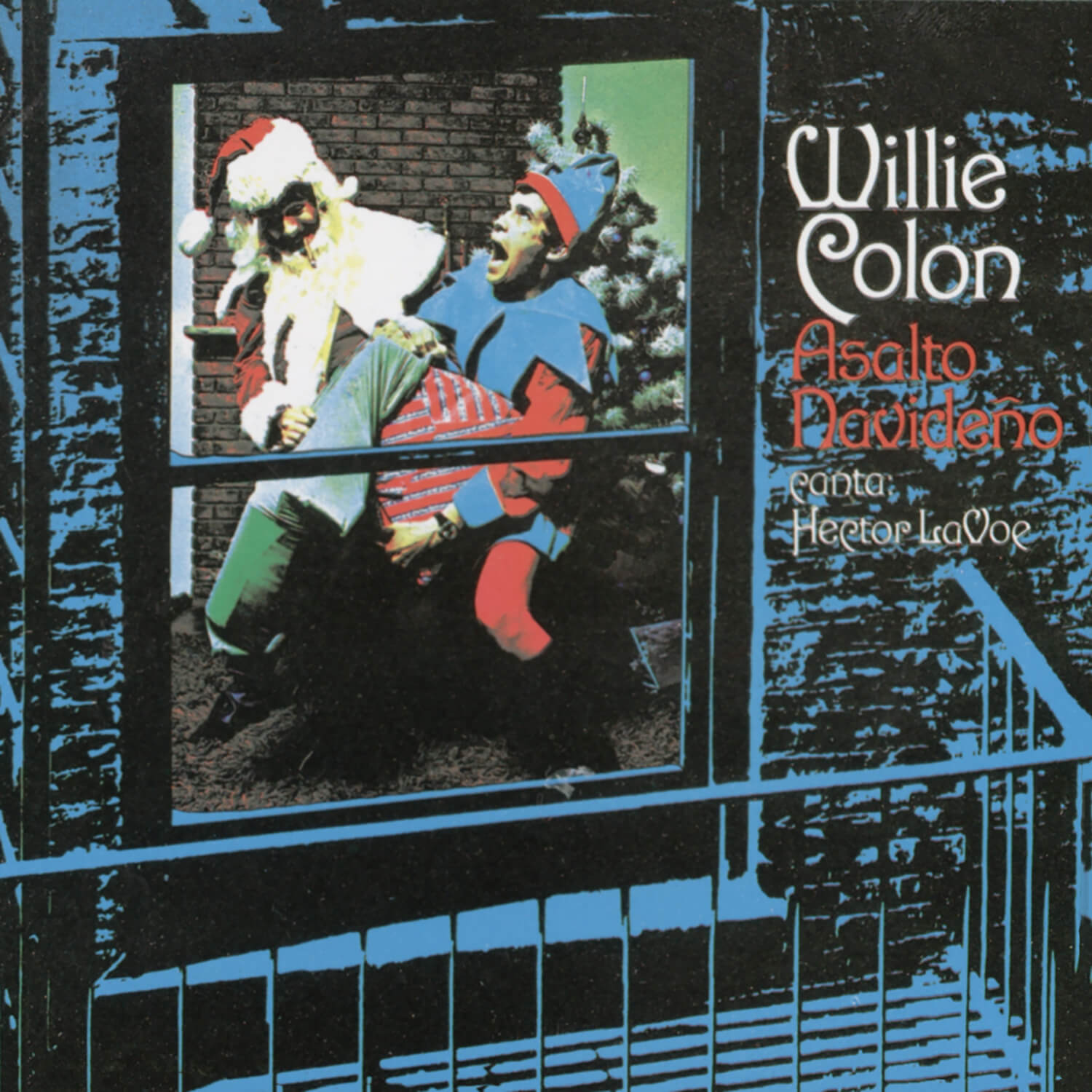

Willie Colón & Héctor Lavoe – Asalto Navideño

Orquesta Novel – Prestige

Fania All Stars – Latin Connection

Eddie Palmieri

Johnny Pacheco & Monguito “El Único” Santamaría – Sabrosura

Celia, Johnny And Pete

Roberto Roena Y Su Apollo Sound 5

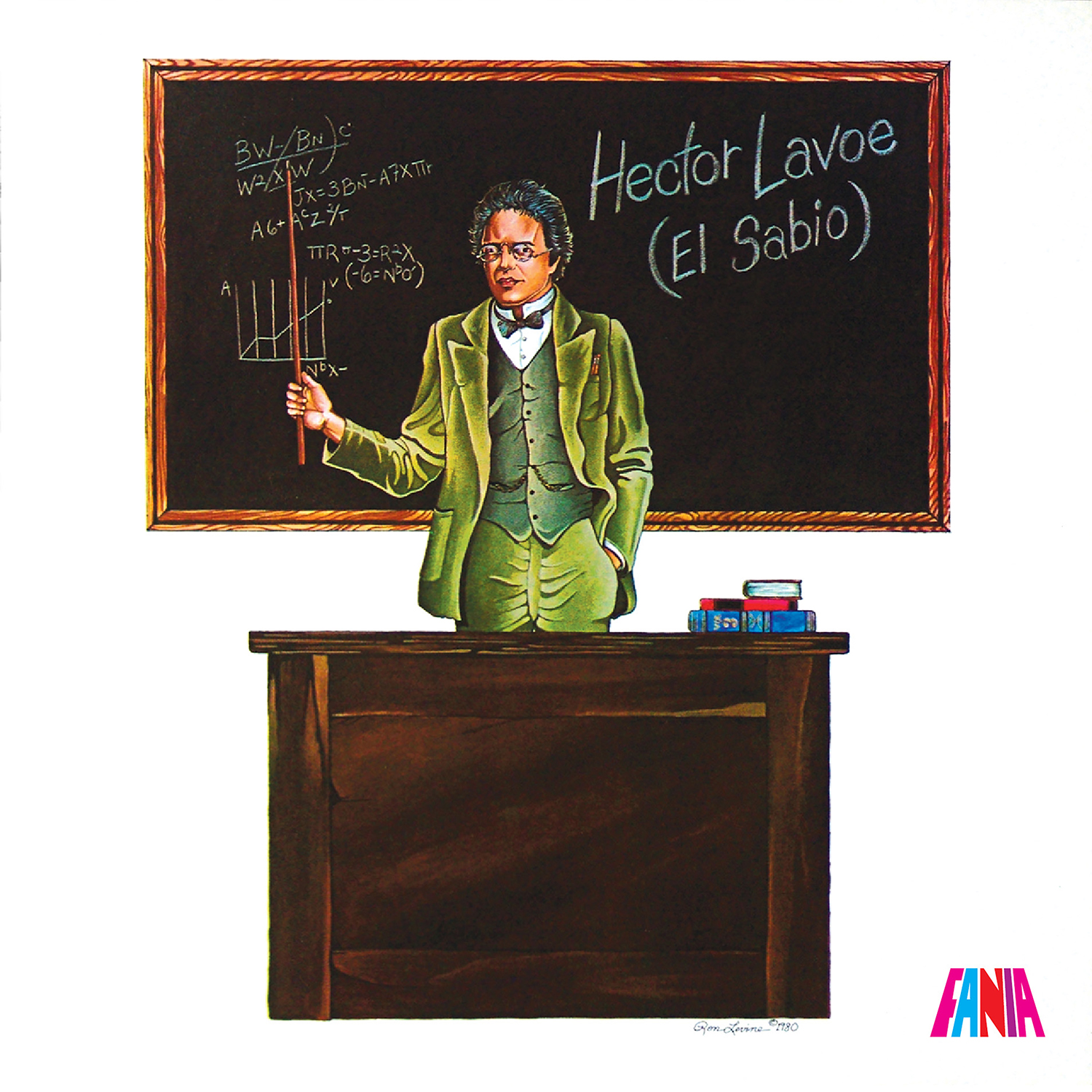

Héctor Lavoe – El Sabio

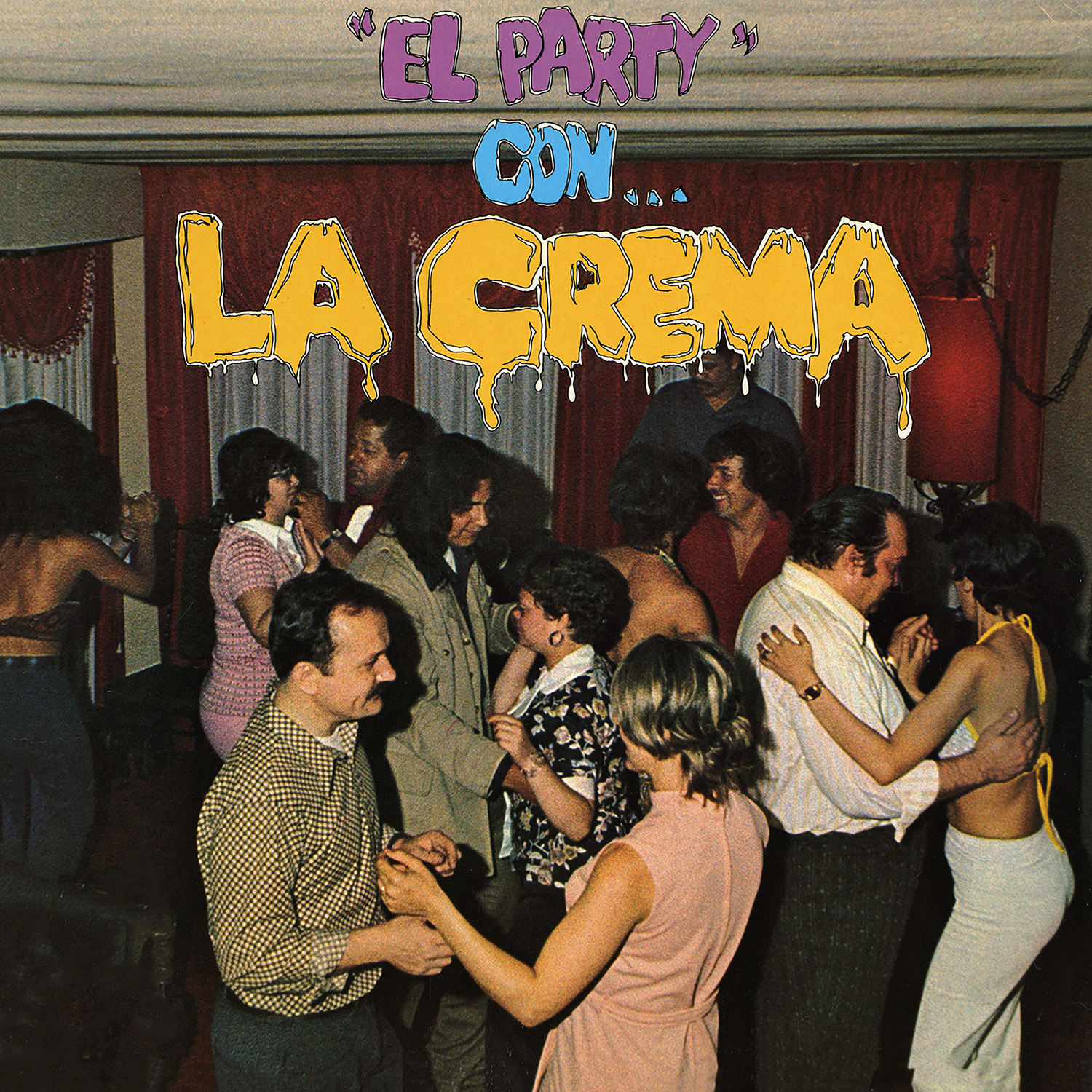

La Crema de New York – El Party

Azuquita Y Su Orquesta Melao – Pura Salsa